世界上最早的医院在苏格兰中部的伊持图塞尔,这座医院建于被罗马军占领时代,有两千年的历史。这座医院建筑物长有100米,宽有70米,地下有完善下水道系统,一间间病房以走廊相连,这表示当时建筑师已知道隔离传染病患者的重要。

其实,世界上最早的医院在我国周代就有了。据《周书·五会篇》记载:周成王在成周大会的会场旁,设过“为诸侯有疾病者之医药所居”的场所,这可视为我国医院的最早雏型。

公元前七世纪,春秋时期最强盛的国家齐国,政治家管仲在首都临淄建立了“养病院”,收容聋、盲、跛、蹩等病人集中疗养。 汉代汉武帝刘彻在各地设置医治场所,配备医生、药物,免费给百姓治病。据《汉书·平帝本纪》记载,汉代时“元始二年(公元2年),郡国大早蝗,治民疾疫者,舍空邸第,为置医药”。这一记载说明当时曾根据疾病流行的情况,设置似现在的隔离医院。

北魏太和二十一年(公元497年),孝文帝曾在洛阳设“别坊”,供百姓就医用。隋代有“病人坊”,收容麻疯病人。唐开元二十二年(公元734年),设有“患坊”。布及长安、洛阳等地,还有悲日院、将理院等机构,收容贫穷的残废人和乞丐等。

南宋理宗宝佑年间,曾经官至宗正少卿兼中书舍人的刘震孙,在广东建立“寿安院”,“对辟十室,可容十人,男女东西,界限有别”;“诊必工,药必良,烹煎责两童”。此外,这家医院还极注意善后工作.死亡了予以掩埋,病治好了则资助使之返家,可称得上一家慈济医院。

----------

国外最早的医院,约始于八、九世纪欧洲 最初是设立在教堂教会等地 而我国类似医院的组织,最迟在周代就有了 据《周书·五会篇》记载:周成王在成周大会的 会场旁,设过"为诸侯有疾病者之医药所居" 的场所这可视为我国医院的最早雏型 中国历史上在不同时期都出现过很多类似于 医院功能的组织和机构,但多为皆昙花一现 《汉书》卷一二《平帝纪》:「郡国大旱 蝗,民疾疫者舍空邸第,为置医药。」 这是中央政府在灾荒期间的临时举措 在性质和功能上其实就是所谓的公立医院了。

宋元佑四年,苏东坡任杭州太守, 捐献50两私帑,和公家经费合办安乐坊 三年医好一千多病人,是历史上第—个 公私合办医院。宋朝医院规模庞大 数量很多设备完善,并设卖药所也就是门诊部 后改名“和剂局”

【到了元代 阿拉伯医学传入我国,1270年在北京设立 "广惠司"1292年建立"回回药物院"为阿拉伯式 医院,这就是上面提到的最早的中外合营“医院” 忽必烈的长寿就受益于阿拉伯医生爱薛。】

真正意义上的现代 西医医院是19世纪初,传入我国的。1835年 美国医生伯驾(P. Paker)在广州建立医局培养 中国最早的西医医生,并开办了博济医院 1866年设立医学堂。这也是中国最早的西医学 专科教育机构】

中国最早自办的西医学院是天津总医院 附设西医学堂又名北洋医学堂、天津军医学堂 1893年由清政府接办天津医学馆改建而成 后改名天津海军医学校。1930年停办。

国立上海医学院是中国历史上唯一的 国立医学院;由国立中央大学医学院 1932年独立建校而成。

西医学教育发源地

1837年,伯驾医生招收三名青年授传医术,成绩最佳者属关韬。至此,中国西医学教育源起。 1865年正式开班,学生八人,学制三年;1897年学生激增,学制改为四年。1902年成立医校——南华医学校,附属博济医院。1930年7月博济医院移交岭南大学。1935年成立岭南医学院。

中国第一位留学医学生黄宽 毕业于爱丁堡医科大学,1856年回国 开创中国女生学医先河 (1879年开始招收女生2名,其中张竹君成为 我国最早的知名女西医)

伟人的光辉 1886年,中国伟大的民主革命先驱孙中山先生投博济医院学医,并开始革命运动。其自云:予自乙酉中法战败年,始决倾覆清廷,创建民国之志,由是以学堂为鼓吹之地,以医术为入世之媒。 岭南大学校董会有感于孙逸仙博士与博济医院之密切关系,决定筹建“孙逸仙博士纪念医院”(即岭南医学院)。1935年11月大楼奠基。

-----

清朝[沪]

1844年,中国医院(仁济医馆)开办,是上海首家西医医院。到1910年,上海地区19所医院共有2100多张床位,占全国医院总数8.4%。1880年,圣约翰书院首设医科,为上海最早的医学堂。1886年,中国博医会成立。20世纪初,上海不断对外交流学习,成为了当时中西方医学交流的中心。

-----------

西医学教育发源地

1837年,伯驾医生招收三名青年授传医术,成绩最佳者属关韬。至此,中国西医学教育源起。

1865年正式开班,学生八人,学制三年;1897年学生激增,学制改为四年。1902年成立医校——南华医学校,附属博济医院。1930年7月博济医院移交岭南大学。1935年成立岭南医学院。

中国第一位留学医学生黄宽

毕业于爱丁堡医科大学,1856年回国

开创中国女生学医先河

(1879年开始招收女生2名,其中张竹君成为

我国最早的知名女西医)

伟人的光辉

1886年,中国伟大的民主革命先驱孙中山先生投博济医院学医,并开始革命运动。其自云:予自乙酉中法战败年,始决倾覆清廷,创建民国之志,由是以学堂为鼓吹之地,以医术为入世之媒。

岭南大学校董会有感于孙逸仙博士与博济医院之密切关系,决定筹建“孙逸仙博士纪念医院”(即岭南医学院)。1935年11月大楼奠基。

---------

https://www.zhihu.com/question/27939411/answer/48090860

【中国最早创立的医学院】天津总医院附设西医学堂(又名北洋医学堂),中国政府最早自办的西医学堂。亦称“天津医学堂”。光绪十九年(1893)由清政府接办天津医学馆(1881 年伦敦传教会 Maehenrie 医生所办)改建而成,附设于李鸿章创办的天津总医院内。主要造就海陆军外科医生。天津总医院副医官林联辉任校长,天津税务署英国医官欧士敦监督一般医学事宜。教习均由医学生出身、已充医官者担任。学生以20名为额,挑选极为严格。课程按西方医学校标准,设置生理学等多门。重视“临症”,课堂学习半年,医学门径略能领悟后,即按日轮班,随医官往医院诊视。学习年限 4 年,学成后发给执照,准以医学谋生。1915 年改名天津海军医学校。1930年停办。

-----------

百度百科伯驾条目的介绍说伯驾是“美国利用宗教侵略中国的代表人物”、“第一位来到中国的基督教传教医生”。实际上,1807年英国伦敦会来华的传教士罗伯特•马里逊(Robert Morison) 1820年在澳门也开设过诊所,尽管是中式诊所,但雇有中西医师,提供免费医疗服务。

1827年,东印度公司的医生郭雷枢(Thomas .R .Colledge)参与其中,开设眼科医馆,医务日增,求诊者每天有40人之多。从1827年到1832年的5年中,共治愈患者4000多人[3]。但可能是因其规模相对还较小,又没有延续下来,因此,一般还是以伯驾的博济医院为中国的第一家现代医院。

------------

Thomas .R .Colledge

https://wenku.baidu.com/view/439b9421482fb4daa58d4bc6.html

Thomas Richardson Colledge (11 June 1797 – 28 October 1879) was an English surgeon with the East India Company at Guangzhou (Canton) who served part-time as the first medical missionary in China, and played a role in establishing the Canton Hospital. In 1837 he founded and served as the first president of the Medical Missionary Society of China.

Dr. Colledge's ophthalmology clinic in Macau

Colledge and his wife Caroline

Colledge and his wife Caroline

Colledge was born in Kilsby Northamptonshire on 11 June 1797, and received his early medical education under Sir Astley Cooper, before formal training (late in life) at Aberdeen Universitygraduating MD in 1839, aged 43.[1]

He earlier had found a position with the Honourable East India Company and through them practised inCanton and Macau and some other Chinese ports, first under the Hon. East India Company, and then under the crown, and was superintending surgeon of the Hospitals for British Seamen.

During his residence in Canton and Macau he originated the first infirmary for the indigent Chinese, which was called after him, Colledge's Ophthalmic Hospital. He was also the founder, in 1837, of the Medical Missionary Society in China, and continued to be president of that society to the time of his death. On the abolition of the office of surgeon to the consulate at Canton in May 1841, and his consequent return to England, deep regret was expressed by the whole community, European and native, and a memorial of his services was addressed to her majesty by the Portuguese of the settlement of Macau, which caused Lord Palmerston to settle on him an annuity from the civil list. Before he left Asia, Colledge mentored an American surgeon, Peter Parker, who became the first full-time medical missionary to the Chinese.

Colledge took the degree of M.D. at King's College, Aberdeen, in 1839, became a fellow of theRoyal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 1840, a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh1844, and a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, England, 1853.

The last thirty-eight years of his life were spent in Cheltenham, where he won universal esteem by his courtesy and skill. He died at Lauriston House, Cheltenham, 28 Oct. 1879, aged 83. His widow, Caroline Matilda, died 6 Jan. 1880.

- A Letter on the subject of Medical Missionaries, by T. R. Colledge, senior surgeon to his Majesty's Commission printed at Macau, China, 1836

- Suggestions for the Formation of a Medical Missionary Society offered to the consideration of all Christian Nations Canton, 1836.

October 2001

Thomas ColledgeA Pioneering British Eye Surgeon in China

Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1530-1532. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.10.1530

Popular opinion of medical missionaries has undergone wide swings during the last 2 centuries. Individuals who traveled far from home, often into dangerous territory to spread their religious faith in conjunction with medical care, have been both praised enthusiastically for their benevolent work, and castigated as pompous, presumptuous, and overly pious.1(vii) Considering the enormous effect these Europeans and Americans had in Asia, Africa, and South America, they are little remembered today.

One of the first Western-trained physicians to go to China was an Englishman, Thomas Richardson Colledge, MD (1796-1879).2 After completing his medical education at St Thomas's Hospital in London, Colledge entered the service of the East India Company, the powerful mercantile firm. He practiced medicine in China, at Macao and Canton. He was employed initially by the East India Company, and later by the British government as a surgeon to the consulate at Canton. He also offered his services gratis to the native population. Very few Western-trained physicians had ever treated the Chinese before. In 1827 he created, in Macao, the first institution to offer Chinese people Western medical care. Known as Colledge's Ophthalmic Hospital, it was available for all types of disease but concentrated on ocular problems. Quickly, Dr Colledge became very busy and treated about 4000 patients throughout the next few years.

Macao is an island off the south coast of China, less than 100 miles downriver from Canton, and is now known as Guangzhou. It became the first permanent European foothold in China in 1557. By the time Colledge arrived there, it had been under Portugese colonial control for nearly 300 years. In 1999, after more than 4 centuries of European domination, Macao reverted to Chinese control, as has Hong Kong, and both are now integral parts of the People's Republic of China. Early in the 19th century, the island of Macao was an easier place for a foreigner to live than the mainland city of Canton. The Chinese placed severe restraints on foreign interaction with natives, allowing only limited relationships with tradesmen. In Canton, foreigners were restricted to a tiny waterfront trading area on the Pearl River. Foreign women were excluded from Canton, and if brought out to China, they lived at Macao.

Westerners were not exactly welcomed with open arms by the Chinese government at that time. They were officially considered barbarians, "foreign devils," and were spied upon. Missionaries were forbidden, as was study of the Chinese language. However, Western medical practitioners were able to influence popular opinion through their care and created more respect for Western institutions than did any other aspect of their civilization, including military force. They opened up China "at the point of a lancet."3 Western medicine may not have led Chinese medicine in terms of pharmacologic agents, but it was far ahead in surgical skill and in understanding of anatomy. Nothing in the Chinese medical system could match the propaganda value of curing blindness through a quick operation. The Chinese had not created much of a medical system. Chinese practitioners were not particularly well trained and there was no overall organization to medical education. No degree or diploma was required to practice. Physicians held little status, and surgeons were held in even lower esteem. Very few procedures were done, the notable exceptions being castration to create eunuchs for the Imperial court, draining pus, and closed reduction of fractures. A strong religious bias against disfiguring the human body discouraged surgery. Medical missionaries from abroad found the field wide open for their work and became influential. Cataract surgery was one of the most common surgical procedures performed by the missionary physicians. The technique was couching—displacing the lens into the vitreous. This was a rather simple method, with generally good results. The tiny incision could be made quickly and with little discomfort. Cataract extraction, pioneered by Jacques Daviel in France in the mid 18th century, was a far more formidable procedure than couching in the era before the development of local anesthesia and antisepsis. Extraction required a larger incision, took more time, and entailed a much higher risk, particularly from vitreous loss and infection. The only other ocular procedures done with any frequency were pterygium excision and repair of entropion due to trachoma.

Colledge practiced medicine during the period when ophthalmology was just beginning to emerge as a specialty. He devoted the majority of his energy to eye care. He was a good friend of and mentor to a young American physician, Peter Parker, MD (1804-1888), who came to China 7 years after Colledge and eventually developed worldwide fame for his work there.4 Colledge was primarily a surgeon employed by a trading company and the British government, and secondarily a medical missionary. Parker, who was educated at the Yale divinity and medical schools, was a missionary first and a physician second. Parker wrote why he, and presumably Colledge, were so interested in ophthalmology:

Diseases of the eye were selected as those the most common in China; and being a class in which the native practitioners were most impotent, the cures, it was supposed, would be as much appreciated as any other.5

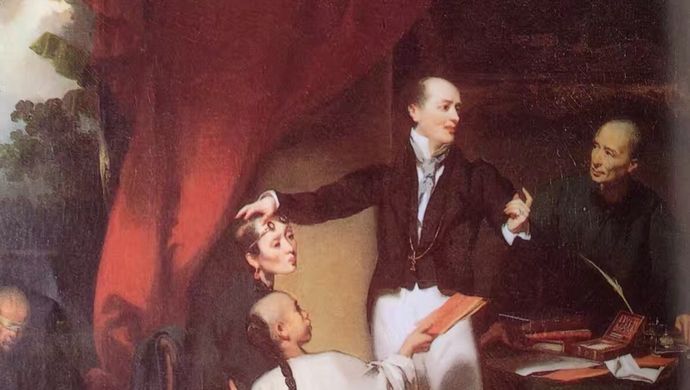

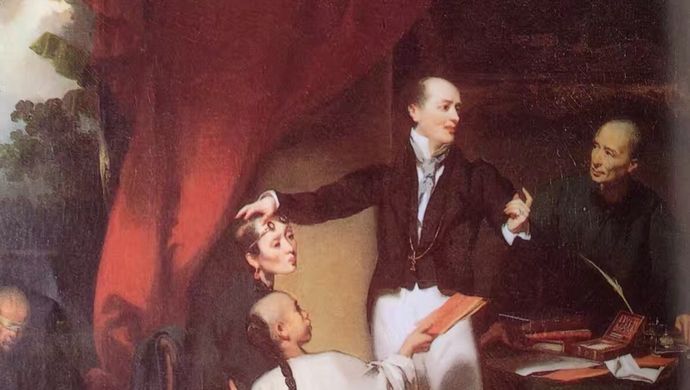

George Chinnery's Portrait of Thomas Colledge in His Study(Figure 1) shows the doctor in a clinical setting. The artist of the original painting is George Chinnery, an English expatriate who spent 27 years on the China coast and specialized in exquisitely brilliant, fashionable portraits. Notes made by a young American woman who watched the artist help us understand the scene.6,7 On the floor in the far left is a Chinese peasant who faces downward. A sash-like bandage covers his eyes, indicating he has just undergone eye surgery. Seated on a Western style chair is a Chinese woman whose delicate features, especially her red pursed lips, rouged cheek, earring, and glasses give her a stylish appearance. Her coat is draped over the back of her chair. On the floor in front of her lay an umbrella and straw hat. Colledge steadies her head with his right hand, while motioning with the other hand to his Chinese servant to come closer and translate instructions for her care. The woman's son, whose long braided queue stands out on his back, kneels before Colledge and presents him with a chop, a thank-you note on red paper. The boy's bare feet and simple costume contrast with the physician's outfit. Colledge looks elegant in his black jacket, cravat, and upturned collar. The chains about his neck and pinkie ring give him something of a foppish look, but he is the center of attention. As the most upright individual depicted, he is the authority figure. His calm nature contrasts with the weather. The dense gray cloud in the sky, the woman's coat, hat, and umbrella indicate rain. On the table in front of the servant are notebooks, papers, writing implements, and a set of surgical instruments. A beautiful wooden case, lined in fabric, contains forceps, scissors, and other ivory-handled instruments. In the upper left corner of the scene are a few formula features added for interest's sake: a red curtain, an urn on a ledge, and a landscape which gives depth and interest to the setting. Oriental foliage gives way to gray clouds and rays of bright sun beyond. The upper right corner of the canvas shows a framed painting of Colledge's ophthalmic hospital.

After working in China for several years and treating thousands of patients, Colledge, still young, went back to England in 1838, never to return to Asia. Why did he leave abruptly? Overwork has been said to be the cause,1(p45) but is unlikely to have been the real reason. His governmental position was discontinued, but this may not have prevented him from continuing to treat the expatriate community and to provide privately funded care free to the Chinese. Poor surgical results or bad relations with other personnel cannot have been the reason either, since on his return to England "deep regret was expressed by the whole community, European and native, and a memorial of his services was addressed to her majesty by the Portugese of the settlement of Macao.8-10 He was granted an annuity by the British government. The most important reason for Colledge's departure from China may be buried in the East India Company Cemetery at Macao, where the remains of 3 of his children still lie today.11 In 1833 Colledge married Caroline Shillaber, a beautiful young woman from an American family living in Macao. Her brother was the American Consul at Batavia (Jakarta). They must have been devastated by the deaths of 3 of their 4 children born to them in China during the next few years. Life could be short on the south China coast, especially for children. Even for missionaries, life expectancy away from home was low everywhere—less than 10 years. It was a hazardous occupation. The voyage out took months and was dangerous due to weather, the treacherous coastline, and pirates. The outposts were isolated and often disease ridden; not really romantic or adventurous places.

Colledge left Macao for England in April, 1838, 1 month after their fourth son was born. The baby died 8 months later. Six weeks after that unpleasant event, Mrs Colledge and their sole surviving child sailed for England. Colledge may have departed before the rest of his family under governmental orders since he still held the rank of Senior Surgeon of the British Medical Service. Peter Parker took over Colledge's role as medical missionary ophthalmologist to Macao and Canton.

Drs Colledge and Parker, supported by a Protestant clergyman, founded the Medical Missionary Society of China, the first medical missionary society in the world. By the time it was formally inaugurated, Colledge had left for England. He remained President of the society until his death, 42 years later. Excerpts from an address by Colledge, which describes the original goals of the society, reveal his thinking:

The great object of this Society, is to aid the Missionary of the Gospel, and the Philanthropist, in the execution of their good works, by opening avenues for the introduction of those sciences and that religion, to which we owe our own greatness . . . Nothing has been attempted in the medical line with the Chinese that has not met with success; the immediate effects have been good, and when moral and religious instruction shall be united with the healing art, who can say where the influence of such a union shall end? The minds of this people must be gradually prepared for the reception of religious and moral principles, and the surest way to accomplish this, will be by showing them the effects of these principles on our own conduct. They are not capable of understanding abstract truths, but facts and actions speak for themselves. . . The practice of medicine by the Chinese physicians is blended with childish superstitions; and surgical aid cannot be procured even by the opulent, for the practice of surgery in any useful form is unknown among them. The influence then of those who restore them to the exercise of their powers is easily accounted for.12

Unfortunately, Colledge has left us only his remarks on the missionary aspect of his thought and not the details of medical care. He obtained an MD degree (an advanced degree in Great Britain, beyond that necessary to practice medicine), from King's College, Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1839. Later, he became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, Scotland; the Royal Society of Edinburgh; and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. He spent his last 38 years in Cheltenham, England, where he practiced medicine and"won universal esteem by his courtesy and skill"2 and the admiration of those around him.

Accepted for publication March 30, 2001.

Corresponding author: James G. Ravin, MD, 3000 Regency Ct, Toledo, OH 43623 (e-mail: jamesravin@aol.com).

1.

Gulick EV Peter Parker and the Opening of China. Cambridge, Mass Harvard University Press1973;

2.

Thomas Richardson Colledge.

Dictionary of National Biography 11 London, England Smith Elder1887;331

Google Scholar

3.

Cadbury WW At the Point of a Lancet: One Hundred Years of the Canton Hospital. Shanghai, China Kelly & Walsh1935;7

5.

Roland CGKey JD Was Peter Parker a competent physician?

Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53123- 127

Google Scholar

6.

Hillard K My Mother's Journal: A Young Lady's Diary of Five Years Spent in Manila, Macao, and the Cape of Good Hope from 1829-1834. Boston, Mass G H Ellis1900;192

7.

Conner P George Chinnery 1774-1852: Artist of India and the China Coast Woodbridge. Suffolk, England Antique Collectors Club1993;222- 224

11.

Ride LRide M An East India Company Cemetery: Protestant Burials in Macao. Hong Kong Hong Kong University Press1996;175- 177

12.

Colledge TR The Medical Missionary Society in China. Philadelphia, Pa Medical Missionary Society1838;4

-----------

为何中国最早的西医医院都从治疗眼病开始?

来源:上观新闻 作者:方益昉 2017-04-03 13:06

摘要:从技术上说,传教医生关注常见病,贴近老百姓,这样的医疗路径探索是成功的。其社会效应是,传教医生为当地百姓缺医少药的情况提供了一定的实质性补充。

1834年10月26日,美国长老会派遣耶鲁大学毕业的医学博士皮特·派克(Peter Parker,清代通事旧译“伯驾医生”者)启程远赴广州。历经一年折腾,伯驾医生最终在十三行的猪巷(HOG LANE)3号, 即新豆栏7号丰泰行(Fung-tae Hong,San-taulan Street)升匾开张,此事被学界标记为传教医生入华执业的源头。

伯驾诊所 关乔昌画 1839年

在1835年11月4日的“眼科医局”(又称新豆栏医局)首日的工作志中,伯驾这样记载:“一共来了4个求诊者。其中一位是双眼全瞎的女性,另一位双眼视力几乎丧失。”但伯驾不忍告诉患者,恢复视力机会渺茫,声称会竭尽全力治疗。还有一位25岁的慢性红眼症患者,第4位患者双眼翼状胬肉,伴右侧上眼睑内翻。

此后,伯驾免费提供医疗服务,一年里诊治的患者累计8000余人。其施医规模与眼疾处置相对快速、疗效稳定不无关系。伯驾继而诱使病患听从上帝呼唤,实现西方教会派遣传教医生,传播福音的主要意图。

其实,早在伯驾之前,东印度公司雇用的专业医生已落户澳门行医。他们是:曾任Arniston号商船外科医生的皮尔森(Alexander Pearson,1802年来华);先后担任过Lord Thurber号、Cirencester号和Coutts号商船外科医生的利文斯通(John Livingstone,1808年来华);做过5年商船外科医生的郭雷枢(Thomas Richardson Colledge)和Caledonia商船外科医生伯莱福特(James H. Bradford)。后两者来华稍迟,分别为1826年和1828年。

隶属东印度公司的临床医生主要为本公司定居商人和流动船员提供不测之需。但当年外籍人员稀疏,这几位医生也为当地民众不时提供西医服务,此事有图有真相,比如流传甚广的英国画家乔治·欣纳利作品——郭雷枢医生诊所,与伯驾专用画师关乔昌的作品一样,两幅油画都在呈现本地眼疾患者,接受医生治疗的现场实景。

19世纪的剃头行当手艺全

轮到更晚一辈的传教医生来华施医送药并传播上帝福音的时候,鸦片战争已经结束。以往各色外籍人等不得擅自离开十三行“自贸区”的“旧皇法”被废,五口通商使得西医传播的社会条件空前松动。于是,各路医学传教士各显神通,到处尝试设立医院,包括英国伦敦会派遣的医学博士洛柯哈特(William Lockhart,旧译雒魏林)。

在更早的几年前,雒魏林已经开始在香港协助行医传教。1843年后,他特意前往宁波舟山,先后2次开张新式医院。但是计划不如变化,当他意识到上海即将成为经济中心时,便立即将西式“上海医馆”,即仁济医院前身的招牌,于1844年挂在了上海老城的东门外闹市中。

像所有的入华西医前辈一样,拥有皇家外科学会头衔的雒魏林外科大夫,还是照旧打出专治眼病的特色项目,吸引本地民众前来接受医疗服务,意在迅速扩大上帝福音范围。从广州、澳门到上海,洋医生均以眼科治疗拓展西医,一定程度上与19世纪常见病特点有关。

还是以雒魏林落脚的黄歇浦与洋泾浜交界处为例,沿袭百年的药局弄、大夫坊上,尽管医疗服务行当云集,但在170多年前,传统岐黄术并不热衷眼病治疗。相反,大清皇土最流行的剃头担子倒是眼明手快,不仅承担了皇上规定的剃发行当,还及时介入刮眉、按摩、挖耳、拔牙、甚至“刮沙眼”服务,眼、耳、鼻、口一条龙,项目之多难以想像!

而眼疾流行,恰恰与剃头匠有关。在没有抗菌素眼药水的19世纪,眼睑微生物感染和季节性传播往往导致结膜炎爆发,俗称红眼病。此病反复发作,极易继发睫毛倒刺,从而更加引起眼睑结膜刺激,红、肿、痛、热,沙眼衣原体密布,眼睑菌落水泡成灾。

上海开埠初期洋泾浜写真

剃头匠说,那就刮沙治疗呗!一把污染的剃刀,刺破过无数菌落,暂时缓解眼部症状,却加剧了眼疾的交叉感染。有些自以为是的匠人,有意将患者眼睑内侧的泪腺剔除,据说可以根除内毒外侵,结果引来结膜炎频发,结缔组织增生,严重者危及角膜感染,甚至失明。剃头匠的不当处置,使得眼疾在人口密集的人群中越发不可控制地流行开来。

害人剃头匠,治病洋医生。2011年,美国国立卫生研究院(NIH)论文分析了19世纪大清帝国的眼疾发病和病患处理,为西医东渐之初从眼科着手,引进西医提供了逻辑依据。通过快捷有效的治疗,让信众一目了然体验了西医手术,眼见为实感受了症状缓解和抗感染疗效。被中医文化主导了2000年的国度,民众逐步认可接受西方医术,继而信仰西方宗教。

从技术上说,传教医生关注常见病,贴近老百姓,这样的医疗路径探索是成功的。其社会效应是,传教医生为当地百姓缺医少药的情况提供了一定的实质性补充。也就是说,在官府老爷压根不相信红毛番鬼还能治病救人的年代,年轻的花旗佬伯驾和英国佬雒魏林等洋医生凭借西医好手艺,不仅赚到治病救人的好名声,也确实促进了社区健康。

不过,毕竟早期传教医生来华目的主要是扩大教会影响力,尤其在西医规模弱小,医院建制化尚未落实的19世纪上半叶,传教比重更加突出。雒魏林热衷传教胜过行医,平时将医院交下属运营,甚至不顾皇法,远赴青浦县城干事业,成为史上“青浦教案”主角。

还是应了那句老话:好事难进门,坏事传千里!西医治病与西医传教,在19世纪社会史上毁誉各半,理应成为西医东渐中值得重新检验的一卵双生学术命题。

(作者系旅美学者、上海交通大学海外教育学院教授,黄杨子整理编辑 原题:关注常见病、贴近老百姓:从仁济医院开创者雒魏林谈早期西医诊治策略 图片来源:方益昉 提供 题图说明:郭雷枢诊所 乔治·欣纳利画 1835年 图片编辑:徐佳敏)

Colledge and his wife Caroline

Colledge and his wife Caroline

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Colledge, Thomas Richardson". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Colledge, Thomas Richardson". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.