When did your formal education in philosophy start?

I didn’t think I was going to study philosophy. I also loved science, and took out lots of books about science as a kid, and, oh gosh, I ruined my mother’s kitchen by trying to do do-it-yourself chemistry experiments. There were all kinds of things that interested me. One of the things about philosophy is that you don’t have to give up on any other field. Whatever field there is, there’s a corresponding field of philosophy. Philosophy of language, philosophy of politics, philosophy of math. All the things I wanted to know about I could still study within a philosophical framework.

What did your religious family think about your pursuit of philosophy?

It made my mother intensely uncomfortable. She wanted me to be a good student but not to take it too seriously. She worried that nobody would want to marry such a bookish girl. But I ended up getting married at 19. And I wasn’t an outwardly rebellious child; I followed all the rules. The problem was, I was allowed to think about whatever I wanted to. Even though I decided very early on that I didn’t believe in any of it, it was okay as long as I had freedom of mind. It was fine with my family.

How early do you think children can, or should, start learning about philosophy?

I started really early with my daughters. They said the most interesting things that if you’re trained in philosophy you realize are big philosophical statements. The wonderful thing about kids is that the normal way of thinking, the conceptual schemes we get locked up in, haven’t gelled yet with them. When my daughter was a toddler, I’d say “Danielle!” she would very assuredly, almost indignantly, say, “I’m not Danielle! I’m this!” I’d think, What is she trying to express? This is going to sound ridiculous, but she was trying to express what Immanuel Kant calls the transcendental ego. You’re not a thing in the world the way there are other things in the world, you’re the thing experiencing other things—putting it all together. This is what this toddler was trying to tell me. Or when my other daughter, six at the time, was talking with her hands and knocked over a glass of juice. She said, “Look at what my body did!” I said, “Oh, you didn’t do that?” And she said, “No! My body did that!” I thought, Oh! Cartesian dualism! She meant that she didn’t intend to do that, and she identified herself with her intentional self. It was fascinating to me.

And kids love to argue.

They could argue with me about anything. If it were a good argument I would take it seriously. See if you can change my mind. It teaches them to be self-critical, to look at their own opinions and see what the weak spots are. This is also important in getting them to defend their own positions, to take other people’s positions seriously, to be able to self-correct, to be tolerant, to be good citizens and not to be taken in by demagoguery. The other thing is to get them to think about moral views. Kids have a natural egotistical morality. Every kid by age three is saying, “That’s not fair!” Well, use that to get them to think about fairness. Yes, they feel a certain sense of entitlement, but what is special about them? What gives them such a strong sense of fairness? They’re natural philosophers. And they’re still so flexible.

There’s a peer pressure that sets in at a certain age. They so much want to be like everybody else. But what I’ve found is that if you instill this joy of thinking, the sheer intellectual fun, it will survive even the adolescent years and come back in fighting form. It’s empowering.

What changes in philosophy curriculum have you seen over the last 40 years?

One thing that’s changed tremendously is the presence of women and the change in focus because of that. There’s a lot of interest in literature and philosophy, and using literature as a philosophical examination. It makes me so happy! Because I was seen as a hard-core analytic philosopher, and when I first began to write novels people thought, Oh, and we thought she was serious! But that’s changed entirely. People take literature seriously, especially in moral philosophy, as thought experiments. A lot of the most developed and effective thought experiments come from novels. Also, novels contribute to making moral progress, changing people’s emotions.

Right—a recent study shows how reading literature leads to increased compassion.

Exactly. It changes our view of what’s imaginable. Commercial fiction that didn’t challenge people’s stereotypes about characters didn’t have the same effect of being able to read others better, but literary fiction that challenges our views of stereotypes has a huge effect. A lot of women philosophers have brought this into the conversation. Martha Nussbaum really led the way in this. She claimed that literature was philosophically important in many different ways. The other thing that’s changed is that there’s more applied philosophy. Let’s apply philosophical theory to real-life problems, like medical ethics, environmental ethics, gender issues. This is a real change from when I was in school and it was only theory.

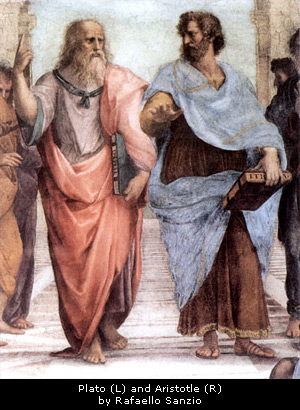

In your new book, you respond to the criticism that philosophy isn’t progressing the way other fields are. For example: In philosophy, unlike in other areas of study, an ancient historical figure like Plato is just as relevant today.

There’s the claim that the only progress made is in posing problems that scientists can answer. That philosophy never has the means to answer problems—it’s just biding its time till the scientists arrive on the scene. You hear this quite often. There is, among some scientists, a real anti-philosophical bias. The sense that philosophy will eventually disappear. But there’s a lot of philosophical progress, it’s just a progress that’s very hard to see. It’s very hard to see because we see with it. We incorporate philosophical progress into our own way of viewing the world. Plato would be constantly surprised by what we know. And not only what we know scientifically, or by our technology, but what we know ethically. We take a lot for granted. It’s obvious to us, for example, that individual’s ethical truths are equally important. Things like class and gender and religion and ethnicity don’t matter insofar as individual rights go. That would never have occurred to him. He makes an argument in The Republic that you need to treat all Greeks in the same way. It never occurs to him that you would treat barbarians (non-Greeks) the same way.

It’s amazing how long it takes us, but we do make progress. And it’s usually philosophical arguments that first introduce the very outlandish idea that we need to extend rights. And it takes more, it takes a movement, and activism, and emotions, to affect real social change. It starts with an argument, but then it becomes obvious. The tracks of philosophy’s work are erased because it becomes intuitively obvious. The arguments against slavery, against cruel and unusual punishment, against unjust wars, against treating children cruelly—these all took arguments.

Which philosophical arguments have you seen shifting our national conversation, changing what we once thought was obvious?

About 30 years ago, the philosopher Peter Singer started to argue about the way animals are treated in our factory farms. Everybody thought he was nuts. But I’ve watched this movement grow; I’ve watched it become emotional. It has to become emotional. You have to draw empathy into it. But here it is, right in our time—a philosopher making the argument, everyone dismissing it, but then people start discussing it. Even criticizing it, or saying it’s not valid, is taking it seriously. This is what we have to teach our children. Even things that go against their intuition they need to take seriously. What was intuition two generations ago is no longer intuition; and it’s arguments that change it. We are very inertial creatures. We do not like to change our thinking, especially if it’s inconvenient for us. And certainly the people in power never want to wonder whether they should hold power. So it really takes hard, hard work to overcome that.

How do you think philosophy is best taught?

I get very upset when I’m giving a lecture and I’m not interrupted every few sentences by questions. My style is such that that happens very rarely. That’s my technique. I’m really trying to draw the students out, make them think for themselves. The more they challenge me, the more successful I feel as a teacher. It has to be very active. Plato used the metaphor that in teaching philosophy, there needs to be a fire in the teacher, and the sheer heat will help the fire grow in the student. It’s something that’s kindled because of the proximity to the heat.

What is it like teaching philosophy to students from a variety of backgrounds?

A good philosophy professor needs to be very aware of the different personalities in her class. I’ve had students who’ve become so very uncomfortable. They needed a lot of handholding. Some came from very religious backgrounds, and just the questioning sent them into a free-fall. We made our way through. Some of them ended up being my strongest students. Two of them are very successful professional philosophers. But they required a lot of extra time because they felt it so deeply. You’re being asked to rethink all sorts of opinions. And when you see that the ground is not very firm, it can distance you from your own family, your upbringing. I went through this. My own philosophical journey distanced me from my family, the people I loved most. That was very difficult, so I know what they’re going through. It can be a very intense journey.

What’s happened to the popularity of philosophy as a subject since you studied it?

It’s gone down. Our college students today are far more practical. When I was in college, which was in the last hey-day of the radical movement, it was a more philosophically reflective time. Now, they want to get good jobs and get rich fast.

Despite this, and the fact that so many students are facing massive debt and a bleak economy, how can you make the case that they should study philosophy?

I wouldn’t say that they must go into philosophy, and frankly, the field can’t absorb that many people, but I would say that it’s always a good thing to know, no matter what you go on to study—to be able to think critically. To challenge your own point of view. Also, you need to be a citizen in this world. You need to know your responsibilities. You’re going to have many moral choices every day of your life. And it enriches your inner life. You have lots of frameworks to apply to problems, and so many ways to interpret things. It makes life so much more interesting. It’s us at our most human. And it helps us increase our humanity. No matter what you do, that’s an asset.

What do you think are the biggest philosophical issues of our time?

The growth in scientific knowledge presents new philosophical issues. The idea of the multiverse. Where are we in the universe? Physics is blowing our minds about this. The question of whether some of these scientific theories are really even scientific. Can we get predictions out of them? And with the growth in cognitive science and neuroscience. We’re going into the brain and getting these images of the brain. Are we discovering what we really are? Are we solving the problem of free will? Are we learning that there isn’t any free will? How much do the advances in neuroscience tell us about the deep philosophical issues? These are the questions that philosophers are now facing. But I also think, to a certain extent, that our society is becoming much more secular. So the question about how we find meaning in our lives, given that many people no longer look to monotheism as much as they used to in terms of defining the meaning of their life. There’s an undercurrent of a preoccupation with this question. With the decline of religion is there a sense of the meaninglessness of life and the easy consumerist answer that’s filling the space religion used to occupy? This is something that philosophers ought to be addressing.

This conversation was edited and condensed for clarity and length.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

作者:李琭璐(女,1987年12月生于北京,中国作家协会会员)

如果因为他是医生,你就无视他的文字,那实在是种可惜。行医与文字,他莫名其妙地生而天赋。初次见面,他正坐在办公室的椅子上,很自在,两条腿拉直伸长,脚尖搭在一起。说起话来慢条斯理,眉毛一跳一跳,双手或摊开或紧握,灵活地传达意思。

他就是郎景和,北京协和医院妇产科主任,中国工程院院士。彼时,一身白衣的他站在窗边接电话,合体的蓝色衬衫,硬朗的脸部线条,侧影挺拔。这位年逾古稀的医者,仿佛电影男主角。他向我笑着伸出右手,得体躬身,发色已然灰白,眼睛仍坦诚年轻,凝视对方。

希臘哲學家亞里士多德曾說:「哲學應該從醫學開始,而醫學最終應該歸隱於哲學。」

赵美娟:解放军总医院-解放军医学院从事以医学博士生为对象的生命哲学、医学哲学、健康哲学等人文领域的讲座与理论研究。解放军总医院“人文讲坛”执行创办人,现为基础教研室主任、教授,现役军人。主编教育部教育科学国家规划项目医药类高校教材《医学人文演讲录》、《医学人文讲坛》等著作。先后负责完成了教育部教育科学国家规划课题、国家社科基金课题、国家社科基金军事学项目课题等,先后获得全军军事科学优秀研究数项成果一等奖、二等奖等。

亚里士多德有一句话:“哲学应该从医学开始,而医学最终应该归隐于哲学。”谈及医学哲学与人文,赵教授在接受采访时表示:“十八年来,我在做医学哲学与人文教育的同时也是通过这个在不断地自我修行,从中理解生命哲学的人文意味。医学走入21世纪取得了巨大的发展,人民的健康也有很大的改善,生命预期和平均寿命都在延长,但现在的很多疾病都是慢性病,因此当今医疗模式存在着反思的空间,这种变化是一个很好的契机,医学哲学在这种情况下是很有借鉴意义的。医学和人文相结合就是为了回归医学本质——以人为本,在观念上如何理解健康和疾病,就意味着在医学上如何干预和处置这个疾病,人文的介入能够更全面地来看待人的整体性,这才是人文最重要的地方。医学不是在修理机器,而是要通过人的心理情感、生活、社会等多方面的整体把握后来认识疾病,要是忽略了人文那就是纯技术操作。”

------------

Aristotle's philosophy was empirical and experiential; he believed in approaching Nature with an open mind to learn Her secrets. ...Aristotle's most important contribution to the theory of GreekMedicine was his doctrine of the Four Basic Qualities: Hot, Cold, Wet, and Dry.

Aristotle's most important contribution to the theory of Greek Medicine was his doctrine of the Four Basic Qualities: Hot, Cold, Wet, and Dry. Later philosopher-physicians would apply these qualities to characterize the Four Elements, Four Humors, and Four Temperaments. The Four Basic Qualities are the foundations for all notions of balance and homeostasis in Greek Medicine.

Aristotle, one the greatest minds that ever existed, is indeed the godfather of evidence-based medicine. His teachings of logic and philosophy have been a driving force continuously guiding medicine away from superstition and towards the scientific method. Today, the revival of evidence-based medicine is only a reaffirmation of his early teachings dating from the fourth century BC.

-------------

Born in 384 B.C.E. the son of a physician at Stageira in Macedonia, Aristotle was one of the most noted philosophers and scientists of the ancient world. Once a student of Plato at his Academy in Athens, Aristotle adopted his own methods of inquiry different from that of his teacher. Unlike Plato, Aristotle felt that one could, and in fact must, trust one's senses in the investigation of knowledge and reality.

Born in 384 B.C.E. the son of a physician at Stageira in Macedonia, Aristotle was one of the most noted philosophers and scientists of the ancient world. Once a student of Plato at his Academy in Athens, Aristotle adopted his own methods of inquiry different from that of his teacher. Unlike Plato, Aristotle felt that one could, and in fact must, trust one's senses in the investigation of knowledge and reality.

At Plato's death, Aristotle was not chosen to be his successor as head of the Academy and he left Athens. He eventually returned to Macedonia, where he was teacher to the young Alexander the Great. After Alexander conquered Athens and the rest of the Middle East and Egypt, Aristotle returned to Athens to found the Lyceum, a school similar to Plato's Academy. After Alexander's death, Aristotle was forced to flee Athens to the nearby island of Euboea, where he died soon afterwards in 322 B.C.E

Aristotle's writings cover a wide variety of subjects, from human and animal anatomy, to metaphysics, statesmanship, and poetry. His treatises on human anatomy are lost, but his many works on animals advocate direct observation and anatomical comparisons between species through dissection. He wrote extensively on the soul, classifying the souls of different forms of life and inanimate objects, including the earth and the heavens. Aristotle wrote extensively on animal life and both sexual and asexual reproduction, making him in many ways the founder of Western natural philosophy.