《论语·颜渊》:“君子敬而无失,与人恭而有礼,四海之内,皆兄弟也。”

四海之内皆兄弟。对应英文:Within the four seas all men are brothers. xx

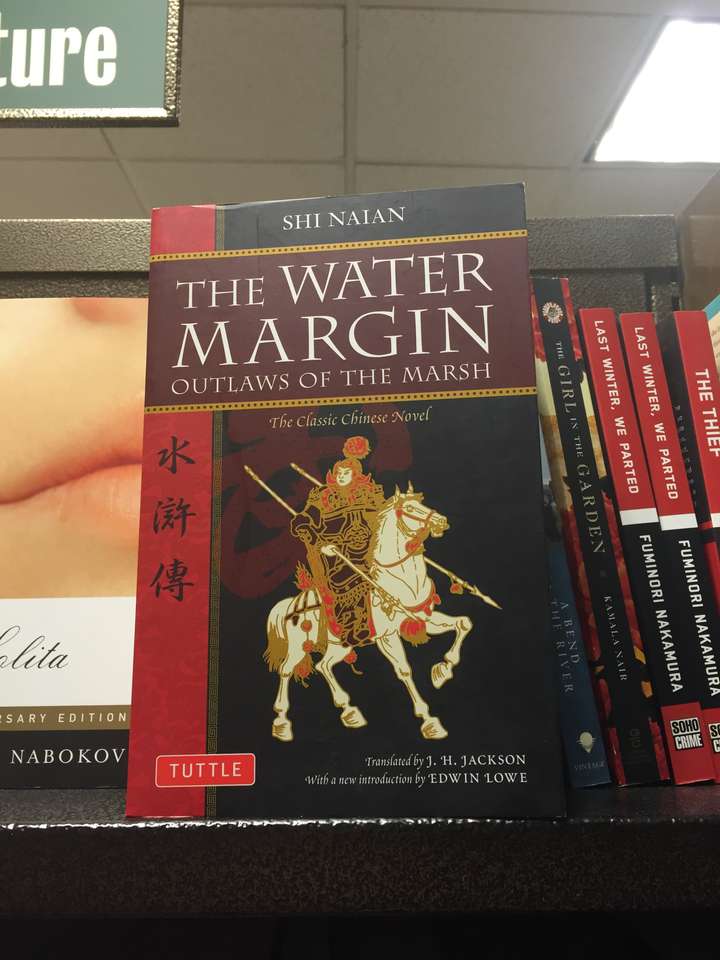

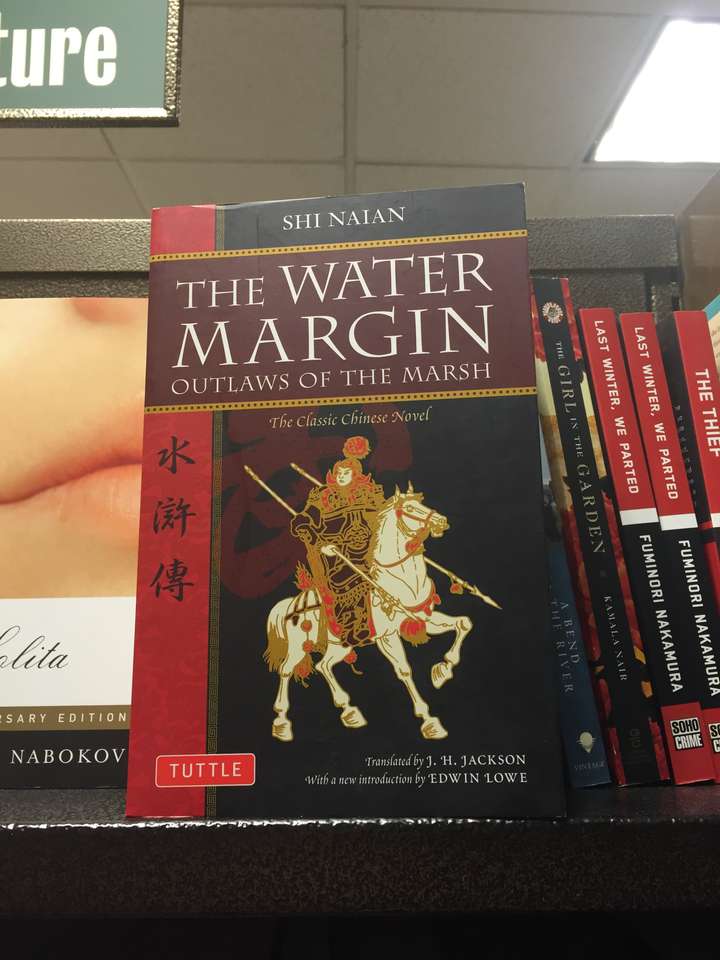

《水浒传》的英译本有四个版本,其中较受欢迎,影响较大的是美国女作家赛珍珠版本的

All Men Are Brothers

赛译以直译为主,尽可能保留了原作的风格和意义,甚至原封不动地保留了一些即使中文读者也不是很感兴趣的内容。

赛珍珠(摄于1938年)

Pearl S. Buck is receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature from King Gustav V of Sweden in the Stockholm Concert Hall in 1938.

------------

Pearl Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973; also known by her Chinese name Sai Zhenzhu; Chinese: 賽珍珠) was an American writer and novelist. As the daughter of missionaries, Buck spent most of her life before 1934 in Zhenjiang, China. Her novel The Good Earth was the best-selling fiction book in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. In 1938, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces".[1] She was the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

After returning to the United States in 1935, she continued writing prolifically, became a prominent advocate of the rights of women and minority groups, and wrote widely on Chinese and Asian cultures, becoming particularly well known for her efforts on behalf of Asian and mixed-race adoption.

Originally named Comfort by her parents,[2] Pearl Sydenstricker was born in Hillsboro, West Virginia, to Caroline Maude (Stulting) (1857–1921) and Absalom Sydenstricker. Her parents, Southern Presbyterian missionaries, traveled to China soon after their marriage on July 8, 1880, but returned to the United States for Pearl's birth. When Pearl was five months old, the family arrived in China, first in Huai'an and then in 1896 moved to Zhenjiang (then often known as Jingjiang or, in the Chinese postal romanization system, Tsingkiang), near Nanking.[3]

Of her siblings who survived into adulthood, Edgar Sydenstricker had a distinguished career with the United States Public Health Service and later the Milbank Memorial Fundand Grace Sydenstricker Yaukey (1899–1994) was a writer who wrote young adult books and books about Asia under the pen name Cornelia Spencer.[4][5]

Chinese man in Zhenjiang, c. 1900

Pearl recalled in her memoir that she lived in "several worlds", one a "small, white, clean Presbyterian world of my parents", and the other the "big, loving merry not-too-clean Chinese world", and there was no communication between them.[6] The Boxer Uprising greatly affected the family; their Chinese friends deserted them, and Western visitors decreased. Her father, convinced that no Chinese could wish him harm, stayed behind as the rest of the family went to Shanghai for safety. A few years later, Pearl was enrolled in Miss Jewell's School there, and was dismayed at the racist attitudes of the other students, few of whom could speak any Chinese. Both of her parents felt strongly that Chinese were their equals (they forbade the use of the word heathen), and she was raised in a bilingual environment: tutored in English by her mother, in the local dialect by her Chinese playmates, and in classical Chinese by a Chinese scholar named Mr. Kung. She also read voraciously, especially, in spite of her father's disapproval, the novels of Charles Dickens, which she later said she read through once a year for the rest of her life.[7]

In 1911, Pearl left China to attend Randolph-Macon Woman's College in Lynchburg, Virginia, in the United States, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1914 and a member of Kappa Delta Sorority. Although she had not intended to return to China, much less become a missionary, she quickly applied to the Presbyterian Board when her father wrote that her mother was seriously ill. From 1914 to 1932, she served as a Presbyterian missionary, but her views later became highly controversial during the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy, leading to her resignation.[8]

In 1914, Pearl returned to China. She married an agricultural economist missionary, John Lossing Buck, on May 30, 1917, and they moved to Suzhou, Anhui Province, a small town on the Huai River (not to be confused with the better-known Suzhou in Jiangsu Province). This region she describes in her books The Good Earth and Sons.

From 1920 to 1933, the Bucks made their home in Nanjing, on the campus of the University of Nanking, where they both had teaching positions. She taught English literature at the private, church-run University of Nanking,[9] Ginling College and at the National Central University. In 1920, the Bucks had a daughter, Carol, afflicted with phenylketonuria. In 1921, Buck's mother died of a tropical disease, sprue, and shortly afterward her father moved in. In 1924, they left China for John Buck's year of sabbatical and returned to the United States for a short time, during which Pearl Buck earned her master's degree from Cornell University. In 1925, the Bucks adopted Janice (later surnamed Walsh). That autumn, they returned to China.[8]

The tragedies and dislocations that Buck suffered in the 1920s reached a climax in March 1927, during the "Nanking Incident". In a confused battle involving elements of Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist troops, Communist forces, and assorted warlords, several Westerners were murdered. Since her father Absalom insisted, as he had in 1900 in the face of the Boxers, the family decided to stay in Nanjing until the battle reached the city. When violence broke out, a poor Chinese family invited them to hide in their hut while the family house was looted. The family spent a day terrified and in hiding, after which they were rescued by American gunboats. They traveled to Shanghai and then sailed to Japan, where they stayed for a year, after which they moved back to Nanjing. Buck later said that this year in Japan showed her that not all Japanese were militarists. When she returned from Japan in late 1927, Buck devoted herself in earnest to the vocation of writing. Friendly relations with prominent Chinese writers of the time, such as Xu Zhimoand Lin Yutang, encouraged her to think of herself as a professional writer. She wanted to fulfill the ambitions denied to her mother, but she also needed money to support herself if she left her marriage, which had become increasingly lonely, and since the mission board could not provide it, she also needed money for Carol's specialized care. Buck went once more to the States in 1929 to find long-term care for Carol, and while there, Richard J. Walsh, editor at John Day publishers in New York, accepted her novel East Wind: West Wind. She and Walsh began a relationship that would result in marriage and many years of professional teamwork. Back in Nanking, she retreated every morning to the attic of her university bungalow and within the year completed the manuscript for The Good Earth.[10]

Pearl Buck in 1932, about the time

The Good Earth was published.

Photo:

Arnold Genthe

When John Lossing Buck took the family to Ithaca the next year, Pearl accepted an invitation to address a luncheon of Presbyterian women at the Astor Hotel in New York City. Her talk was titled "Is There a Case for the Foreign Missionary?" and her answer was a barely qualified "no". She told her American audience that she welcomed Chinese to share her Christian faith, but argued that China did not need an institutional church dominated by missionaries who were too often ignorant of China and arrogant in their attempts to control it. When the talk was published in Harper's Magazine,[11] the scandalized reaction led Buck to resign her position with the Presbyterian Board. In 1934, Buck left China, believing she would return,[12] while John Lossing Buck remained.[13]

Career in the United States[edit source]

In 1935 the Bucks divorced in Reno, Nevada,[14] and she married Richard Walsh that same day.[12] He offered her advice and affection which, her biographer concludes, "helped make Pearl's prodigious activity possible". The couple lived in Pennsylvania until his death in 1960.[10]

During the Cultural Revolution, Buck, as a preeminent American writer of Chinese village life, was denounced as an "American cultural imperialist".[15] Buck was "heartbroken" when she was prevented from visiting China with Richard Nixon in 1972. Her 1962 novel Satan Never Sleeps described the Communist tyranny in China. Following the Communist Revolution in 1949, Buck was repeatedly refused all attempts to return to her beloved China and therefore was compelled to remain in the United States for the rest of her life.[12]

Pearl S. Buck died of lung cancer on March 6, 1973, in Danby, Vermont, and was interred in Green Hills Farm in Perkasie, Pennsylvania. She designed her own tombstone. Her name was not inscribed in English on her tombstone. Instead, the grave marker is inscribed with Chinese characters representing the name Pearl Sydenstricker.[16]

Nobel Prize in Literature[edit source]

In 1938 the Nobel Prize committee in awarding the prize said:

By awarding this year's Prize to Pearl Buck for the notable works which pave the way to a human sympathy passing over widely separated racial boundaries and for the studies of human ideals which are a great and living art of portraiture, the Swedish Academy feels that it acts in harmony and accord with the aim of Alfred Nobel's dreams for the future.[17]

In her speech to the Academy, she took as her topic "The Chinese Novel." She explained, "I am an American by birth and by ancestry", but "my earliest knowledge of story, of how to tell and write stories, came to me in China." After an extensive discussion of classic Chinese novels, especially Romance of the Three Kingdoms, All Men Are Brothers, and Dream of the Red Chamber, she concluded that in China "the novelist did not have the task of creating art but of speaking to the people." Her own ambition, she continued, had not been trained toward "the beauty of letters or the grace of art." In China, the task of the novelist differed from the Western artist: "To farmers he must talk of their land, and to old men he must speak of peace, and to old women he must tell of their children, and to young men and women he must speak of each other." And like the Chinese novelist, she concluded, "I have been taught to want to write for these people. If they are reading their magazines by the million, then I want my stories there rather than in magazines read only by a few."[18]

------------

John Lossing Buck (1890–1975) was an American agricultural economist [1] specializing in the rural economy of China. He first went to China in 1915 as an agricultural missionary for the American Presbyterian Mission and was based in China until 1944. His wife, whom he later divorced, was Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973).

American Southern Presbyterian Mission was an American Presbyterian missionary society of the Southern Presbyterian Church that was involved in sending workers to countries such as China during the late Qing Dynasty.[1]It was organized in 1862.

- American Presbyterian Mission (1867). Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

The Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS, originally Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America) was a Protestant Christian denomination in the Southern and border states of the United States that existed from 1861 to 1983. That year it merged with the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (UPCUSA) to form the Presbyterian Church (USA).

----------

赛珍珠[1](英语:Pearl Sydenstricker Buck,直译为“珀尔· 赛登斯特里克·巴克”,1892年6月26日-1973年3月6日),美国旅华作家,曾凭借其小说《大地》(The Good Earth),于1932年获得普利策小说奖,后在1938年获得诺贝尔文学奖,也是获得普利策奖和诺贝尔奖的第一位女作家,以及作品流传语种最多的美国作家。

1880年美南长老会的传教士赛兆祥携新婚妻子卡罗琳来华,卡罗琳在中国共生了生了二女一男,都死于当时无法防治的“热病”,于是在怀孕第四个的时候,被送回美国休养。1892年6月26日,赛珍珠出生在美国西弗吉尼亚州,起名为康福特(Comfort[2])。到中国以后,改名为珍珠(Pearl),“康福特”变为中间名。父母亲在她出生3个月时一同来到中国江苏清江浦(今淮安市主城区),后来搬到镇江,住在润州山长老会润州中学的平房里(此处故居已经拆除);在那里长大成人,她是先学会汉语和习惯中国风俗(特别受益于其老师“孔先生”)后,她母亲才教她英语。值得一提的是,从幼年起,她就在鼓励中开始写作。

1910年,赛珍珠离开中国,到美国弗吉尼亚州伦道夫·梅康女子学院学习。于1914年获得了学位之后,她又回到中国,并且在1917年嫁绐了农业经济学家约翰·洛辛·卜凯。随后他们举家移居到安徽北部的宿县,在此期间的生活经历成为后来闻名世界的《大地》的素材。在1921年底她的母亲去世后,全家迁到南京,赛珍珠则在金陵大学(今南京大学部分)教授英语文学,并兼执教于南高、东大和中大时期南京大学英语系。1921年,他们有了女儿卡罗(Carol);不幸的是,这个女孩患有苯丙酮尿症。1925年,她收养了贾尼斯(Janice,后改姓Walsh),之后又接着收养了8个孩子。1926年,她小别中国,到美国的康乃尔大学攻读艺术硕士学位。旋即回到中国南京。

1930年,赛珍珠出版了她的第一部作品《东风:西风》,从而开始了她的写作事业。1931年,其著名小说《大地》问世,被后人认为是她最为杰出的作品之一。农民王龙的生活故事使她于1932年获得了普利策奖。她的事业从此蒸蒸日上,并于1935年获得了威廉·迪恩·豪威尔勋章。

然而,1934年中国政局陷入了混乱,赛珍珠被迫离开中国。她回到了美国,这时她的丈夫向她提出了离婚,她同意了。之后又嫁给了纽约出版商庄台公司(John Day Co.)的总裁理查德·J·华尔士,并且又收养了六个孩子。在完成了描写其父母的作品《流亡》和《搏斗的天使》之后,她于1938年获得了诺贝尔文学奖。曾任美国作家协会主席。

在她的一生中,赛珍珠创作了超过100部文学作品,其中最著名的就是《大地》。她作品的题材包括小说,短篇故事,剧本和儿童故事。她的作品和生活有着紧密的联系。她试图向她的读者证明:只要愿意接受,人类是存在着广泛的共同性的。她的作品主题涵养了女性、情感(广义的)、亚洲、移民、领养和人生际遇。

1973年3月6日,赛珍珠在佛蒙特州的丹比逝世,葬于宾西法尼亚州普凯西的绿山农场[3]。

与中国的关系[编辑]

赛珍珠生前曾经多次出入中国教书,并对当地民风和各大事件留下深厚的感情,也因此将之融入到了往后的许多作品当中。

1937年抗日战争爆发后,为中国人民的反侵略战争奔走。许许多多美国人正是通过赛珍珠的小说了解到中国,为中国人民的抗日战争解囊相助。

她出生在基督传教士家庭,但却反对传教。在中国、美国许多地方,她公开声称她极为讨厌那些“喋喋不休的布道”,说传教士布道只会“扼杀思想,蛊惑人心,在中国教会里制造出一批伪君子”。

赛珍珠有许多中国好友,包括徐志摩、林语堂、胡适等人。赛珍珠邀请林语堂在美国发表作品,后来林的《吾国与吾民》在美国一炮而红。林语堂因发明中文打字机破产,曾向赛珍珠借钱遭到拒绝,两人在美国打起出版官司,最后形同陌路。1954年10月,林语堂出任新加坡南洋大学校长前夕,曾打电报向赛珍珠报告,赛珍珠没回电报。林语堂说一句话:“我看穿了一个美国人!”[4]

她因批评蒋介石独裁,国民政府拒绝参加她的诺贝尔文学奖领奖仪式。

她曾经同情中共,赞许毛泽东。认为当时的中共,是“完全为老百姓的事业着想”。由于她同情中国革命,在二战结束后,赛珍珠因“亲共”而上了中央情报局的黑名单,被怀疑是共产党,黑档案长达300页[5]。

由于她对中华人民共和国成立后中共部分做法的批评立场[5],中华人民共和国政府成立后,她的作品在中国大陆长期被打压,大陆文化界攻击她是“美国反动文人”和“美帝国主义文化侵略的急先锋”。[6][7]1972年美国总统尼克松访华两个月后,赛珍珠也向新闻媒体宣布自己即将访华,但随后因为江青(当年蓝苹同王莹争演《赛金花》的主角失败,赛珍珠对王莹捧场[8])的阻拦,遭到中华人民共和国政府拒绝。

在中国江西九江庐山、江苏镇江、安徽宿州、南京大学,至今保存着当年赛珍珠生活过的故居。

1990年代晚期,中美两国展开了一系列围绕赛珍珠的文化交流。2001年罗燕改编赛珍珠小说《群芳庭》并自己担任女主角,由好莱坞环球电影公司和北京电影制片厂联合摄制的电影《庭院里的女人》在中国和美国同时公演。

赛珍珠的英译《水浒传》

顾 钧《 博览群书 》( 2011年04月07日)

赛珍珠(Pearl Buck)是第一个因描写中国而获得诺贝尔文学奖的西方作家(1938年),她对于中国文学特别是中国小说十分推崇。在所有的中国古典小说中,赛珍珠最喜爱、最崇拜的是《水浒传》。从1927到1932年,她用了整整四年的时间翻译了《水浒传》(七十一回本)全文,这是最早的英语全译本。该译本于1933年在美国纽约和英国伦敦同时出版,改书名为《四海之内皆兄弟》(All Men Are Brothers),在欧美风靡一时。后来于1937、1948、1957年在英美再版,有些国家还据赛珍珠译本转译成其他文本。

赛珍珠的翻译是《水浒传》最早的英语全译本,但这不是说,这一译本是原文一字不落的翻译。在翻译的过程中,赛珍珠省略了不少内容,最明显的是,原书的七十一回到译本中只有七十回。究其原因,在于译者将原书的第一回《张天师祈禳瘟疫,洪太尉误走妖魔》并入了《引首》,译文的第一回从《王教头私走延安府,九纹龙大闹史家村》开始。这样删节合并也有一定的道理,因为正是从这一回开始才真正进入小说的正题。此外,译本中将原作中绝大部分诗词删去未译,那些描写人物外貌、打斗场面、山川景物以及日常用品等的诗词歌赋虽然生动、形象,但对于译者来说却是不小的难题。当然这并不是说赛珍珠没有能力翻译这些内容,如原作《引首》开篇的诗词以及著名的“九里山前作战场,牧童拾得旧刀枪;顺风吹动乌江水,好似虞姬别霸王”一诗都得到了很忠实的翻译。赛珍珠表示,她翻译《水浒传》不是出于学术的目的,而“只是觉得它是一个讲的很好的故事”(英文本序言第5页)。从译文的效果来看,不翻译那些时常打断小说叙事的诗文反而有利于故事情节发展的流畅性。同时,与故事情节发展密切相关的诗词赛珍珠全部予以翻译。

除了这些删节之外,赛珍珠的译本基本上可以说是逐字逐句的翻译。赛珍珠在《序言》中表达过这样的雄心:“我尽可能地直译,因为中文原文的风格与它的题材是非常一致的,我的工作只是使译文尽可能像原文,使不懂原文的读者仿佛是在读原文。原文中不精彩的地方,我的译文也不增添。”我们知道,赛珍珠是著名的作家,在翻译这本书的同时还在进行创作,而且她的代表作《大地》(The Good Earth)已在译本完成之前出版并为她赢得了极大的声誉。对一个不仅能翻译,也能创作的译者来说,遇到对原作不满意的地方时往往会技痒,会情不自禁地加上几笔,晚清翻译家林纾就是一个典型的例子(参阅钱锺书《七缀集·林纾的翻译》)。但赛珍珠忍住了没有这么做,她的翻译是相当忠实于原文的,有时甚至过于拘泥于原文,如:To extricate yourself from a difficulty there are thirty-six ways but the best of them all is to run away.(三十六计,走为上策)。至于一百零八将的诨号,赛珍珠也采取了同样的翻译方法:The Opportune Rain(及时雨);The Leopard Headed(豹子头);The Fire In The Thunder Clap(霹雳火);He Whom No Obstacle Can Stay(没遮拦);White Stripe In The Waves (浪里白条);Flea On A Drum(鼓上蚤)。

总的来看,赛珍珠的《水浒传》译本是质量上乘的,这除了她本人对于中、英两种语言的把握之外,也与她的中国友人的帮助分不开。龙墨乡先生在翻译过程中向赛珍珠提供了许多有益的建议,包括解释小说中出现的中国的风俗习惯、武器以及当时已经不再使用的语汇。除此之外,他们还有更为有趣的合作方式:“首先我独自重读了这本小说,然后龙先生大声地读给我听,我一边听,一边尽可能准确地翻译,一句接一句,我发现这种他一边读我一边翻的方式比我独自翻译要快,同时我也把一册《水浒传》放在旁边,以备参考。翻译完成以后,我和龙先生一起将整个书过一遍,将翻译和原文一字一句地对照。”(英文本序言第9页)这种翻译方式让我们很容易想到林纾和他的合作者,但更靠近的例子似乎应该是英国汉学家理雅各(James Legge)和晚清文人王韬合作翻译儒家经典。虽然我们不是十分清楚理雅各和王韬合作的具体细节,但是一个熟悉中外语言的外国人与一个精通中文的中国人一起来翻译中国的著作无疑是相当理想的合作模式。正因为如此,赛译《水浒传》取得了令人满意的结果。

胡适曾将中国古代小说分为两种,一种是“由历史逐渐演变出来的小说”,另一种是由某一作家“创造的小说”。前者如《水浒传》,后者如《红楼梦》。关于前者他写过著名的论文《水浒传考证》,此文的方法正如他后来指出的那样,是“用历史演进法去搜集它们早期的各种版本,来找出它们如何由一些朴素的原始故事逐渐演变成为后来的文学名著”。(《胡适口述自传》,台北传记文学出版社1981年,P194)他用同样的方法考察了李宸妃的故事在宋元明清的流变后,提出了著名的“滚雪球”理论:“我们看这一个故事在九百年中变迁沿革的历史,可以得一个很好的教训。传说的生长,就同滚雪球一样,越滚越大,最初只有一个简单的故事作个中心的‘母题’(Motif),你添一枝,他添一叶,便象个样子了。后来经过众口的传说,经过平话家的敷衍,经过戏曲家的剪裁结构,经过小说家的修饰,这个故事便一天天的改变面目:内容更丰富了,情节更精细圆满了,曲折更多了,人物更有生气了。”(《胡适古典文学研究论集》,上海古籍出版社 1988年,P1193)赛珍珠对此也有很深刻的认识,她在《译序》中说,“《水浒》成长为现在这个样子的过程是一个非常有趣的故事,像很多中国小说一样,它是逐渐发展而来而不是写出来的,直到今天到底谁是它的作者还不知道。”在后来的《中国小说》(The Chinese Novel,1939)一文中,她更进一步地提出了“人民创造了小说”的见解,与胡适的观点相视而笑,甚至可以说归纳得更为深刻。

正因为“水浒故事”是逐渐丰富发展的,所以版本情况十分复杂,今知有7种不同回数的版本,而从文字的详略、描写的细密来分,又有繁本和简本之别。赛珍珠选择七十一回本,并不是因为这是最短的版本,而是她认为七十一回本代表了《水浒》的真精神:“这些章节都是一个人写的,其他版本中后面的章节是别人增加的,主要是写他们的失败和被官府抓住的情形,目的显然是为了将这部小说从革命文学中剔除出去,并用一个符合统治阶级的意思来结束全书。”她认为这样的版本失去了七十一回本“主题和风格所表现的精神和活力”。(英文本序言第7页)赛氏的看法无疑是很有见地的,胡适在1920年顷建议亚东图书馆出版新式标点符号本古典小说时推荐的也正是七十一回本。

选择七十一回本固然大有道理,但赛珍珠似乎没有意识到一个无法回避的尖锐问题:水浒英雄并不是彻底的革命者,正如鲁迅所指出的那样,“一部《水浒》,说得很分明:因为不反对天子,所以大军一到,便受招安,替国家打别的强盗——不‘替天行道’的强盗去了。终于是奴才”。(《鲁迅全集》第4卷,人民文学出版社1981年,P155)好汉们奴性的暴露固然主要是在七十一回之后,但七十一回之前并非没有露出端倪,七十一回并不是好汉们转变的分水岭。选择这个版本可以找到更为坚实的理由:相比后面的章节,这部分情节紧凑、精彩,文笔优美,是精华所在。

赛珍珠对小说中的英雄的理解还有一个偏差。她将英文译本的题目改为“四海之内皆兄弟”,也是有问题的。鲁迅在1933年3月24日致姚克的信中提到赛珍珠的该译本:“近布克夫人(按即赛珍珠)译《水浒》,闻颇好。”但对她改换题目表示了不满:“因为山泊中人,是并不将一切人们都作兄弟看的。”(《鲁迅全集》第12卷,P72)赛珍珠在多年以后承认了自己的错误,并声称当初“不该勉强地答应”出版商的要求而改换题目。但在当时她为自己的做法极力辩护:“英文标题不是中文标题的翻译,它是无法翻译的,Shui的意思是‘水’,Hu的意思是‘边缘或边界’,Chuan对应于英文的‘小说’一词。将这几个字并列起来在英文里几乎是没有意义的,至少在我看来,它会导致读者对本书产生有问题的看法。所以我自以为是地选择了孔子的一句话作为英文标题,这个题目无论从广度上还是从含义上都表达了这帮正义的强盗的精神。”(英文本序言第5-6页)另外,我们还可以为赛珍珠再找一条理由:《水浒》中的人物也多次使用这句话,如原作第二回中陈达和第四回中赵员外。在翻译《水浒传》的四年中,赛珍珠试用过的书名有《侠盗》、《义侠》等,出版前没多久才根据出版商的要求定下《四海之内皆兄弟》的题目。

作者单位:北京外国语大学海外汉学研究中心

------------

The Water Margin J.H.Jackson 版

沙博理,1915年12月生于美国纽约,1937年于圣约翰大学法律系毕业后担任律师。第二次世界大战期间,他应征入伍。之后进入耶鲁大学学习中文。中国灿烂的古代文化和充满创造精神的漫长历史吸引了他,他告别了母亲和祖国,用退伍费买了前往中国的船票,于1947年4月远涉重洋来到中国上海。

新中国最初并没有律师职业,闲不住的沙博理开始尝试着接触新的领域。几十年来,他一直笔耕不辍。作为新中国文学西播的前驱,沙博理翻译了二十余种中国现当代文学作品。20世纪70年代,他开始着手翻译中国古典名著《水浒传》,并赢得中国文联最高翻译奖,使中国的文化经脉在国外的土壤中继续延伸。

如今,94岁的沙博理是全国政协年级最长的委员,中国著名的翻译家,因将《水浒传》译成英语而赢得过中国文联颁发的最高翻译奖。沙博理先生同时也是对外交流家,在新中国成立之后,把自己的一切贡献给新中国的建设,加入了中国国籍,与他的祖国同喜同悲。