本文摘自《文史参考》2010年10月上 翻译:程代熙

1861年,法国文豪维克多·雨果在给他的朋友、参加过第二次鸦片战争英法联军的巴雷特大尉的一封信中,严厉地健责了英法联军在圆明园犯下的罪行,表达了这位文坛巨匠令人尊敬的正义感和坦荡襟怀。

致巴雷特大尉

1861年11月25日

您很想知道我对军事远征中国一事的看法。既然您认为这次远征是一桩豪迈而又体面的事情,那就只好劳驾您对我的看法赋予一定的意义。在您看来,维多利亚女皇和拿破仑皇帝的联合舰队所进行的这次远征真是无上的荣耀,而且还是法兰西和英吉利共同分享的一次荣光,因此您很想知道,我对英法的这次胜利是否有充分的认识。

既然您想听听我的意见,那我就来谈谈我的看法。

在地球上的一个角落里,有一个神奇的世界,这个世界就叫做夏宫。奠定艺术的基础的是这样两种因素,即产生出欧洲艺术的理性与产生出东方艺术的想象。在以想象为主的艺术里,夏宫就相当于以理性为主的艺术中的帕特农神殿。凡是人民--几乎是神奇的人民的想象所能创造出来的一切,都在夏宫身上得到体现。帕特农神殿是世上极为罕有的、独一无二的创造物,然而夏宫却是根据想象拓制出来的一个硕大的模型,而且也只有根据想象才能拓制出这样的模型。您只管去想象那是一座令人神往的,如同月宫的城堡一样的建筑。夏宫就是这样的一座建筑。您尽可以用云石、玉石、青铜和陶瓷来创造您的想象;您尽可以用云松来作它的建筑材料;您尽可以在想象中拿最最珍贵的宝物,用华丽无比的名绸来装饰它;您可以借想象把它化为一座宫殿,一间闺房,一个城堡;您尽管去想象那里住的全是神仙,遍地都是宝;您尽管去想象这座建筑全是用油漆漆过的,上了珐琅的,镀金的,而且还是精雕镂刻出来的;您尽可以在想象中指令那些具有跟诗人一般想象能力的建筑师,把《一干零一夜》中的一千零一个梦表现出来;您也尽可以去想象四周全是花园,到处都有喷水的水池,天鹅,朱镂和孔雀。总之一句话-您尽可以凭人类所具有的无限丰富和无可比拟的想象力,把它想象为是一座庙堂,一座宫殿--这样,这个神奇的世界就会展现在您的眼前了。为了创造它,需要整整两代人成年累月地进行劳动。这座庞大得跟一座城池一样的建筑物,是经过好几个世纪才建筑起来的。这是为什么人建筑的呢?是为世界的各族人民。因为创造这一切的时代是人民的时代。艺术家、诗人、哲学家,个个都知道这座夏宫;伏尔泰就提到过它。人们常常这样说:希腊有帕特农神殿,埃及有金字塔,罗马有大剧场,巴黎有圣母院,东方有夏宫。没有亲眼看见过它的人,那就尽管在想象中去想象它好了。这是一个令人叹为观止的,无与伦比的艺术杰作。这里对它的描绘还是站在离它很远很远的地方,而且又是在一片神秘色彩的苍茫暮色中作出来的,它就宛如是在欧洲文明的地平线上影影绰绰地呈现出来的亚洲文明的一个剪影。

这个神奇的世界现在已经不见了。

有一天,两个强盗闯入了夏宫,一个动手抢劫,一个把它付诸一炬。原来胜利就是进行一场掠夺。胜利者盗窃了夏宫的全部财富,然后彼此分赃。这一切所作所为,均出自额尔金之名。这不禁使人油然想起帕特农神殿的事。他们把对待帕特农神殿的手法搬来对待夏宫,但是这一次做得更是干脆,更是彻底,一扫而光,不留一物。即使把我国所有教堂的全部宝物加在一起,也不能同这个规模宏大而又富丽堂皇的东方博物馆媲美。收藏在这个东方博物馆里的不仅有杰出的艺术品,而且还保存有琳琅满目的金银制品。这真是一桩了不起的汗马功劳和一笔十分得意的外快!有一个胜利者把一个个的口袋都塞得满满的,至于那另外的一个,也如法炮制,装满了好几口箱子。之后,他们才双双手拉着手荣归欧洲。这就是这两个强盗的一段经历。

我们,欧洲人,总认为自己是文明人;在我们眼里,中国人,是野蛮人。然而,文明却竟是这样对待野蛮的。

在将来交付历史审判的时候,有一个强盗就会被人们叫做法兰西,另一个,叫做英吉利。不过,我要在这里提出这样的抗议,而且我还要感谢您使我有机会提出我的抗议。绝对不能把统治者犯下的罪行跟受他们统治的人们的过错混为一谈。做强盗勾当的总是政府,至于各国的人民,则从来没有做过强盗。

法兰西帝国侵吞了一半宝物,现在,她居然无耻到这样的地步,还以所有者的身份把夏宫的这些美轮美奂的古代文物拿出来公开展览。我相信,总有这样的一天--这一天,解放了的而且把身上的污浊洗刷干净了的法兰西,将会把自己的赃物交还给被劫夺的中国。

我暂且就这样证明:这次抢劫就是这两个掠夺者干的。

阁下,您现在总算知道了,我对这次军事远征中国的事情,是有充分的认识的。(原载1962年3月29日《光明日报》,程代熙译)

---------

The sack of the Summer Palace

To Captain Butler

Hauteville House,

25 November, 1861

You ask my opinion, Sir, about the China expedition. You consider this expedition to be honourable and glorious, and you have the kindness to attach some consideration to my feelings; according to you, the China expedition, carried out jointly under the flags of Queen Victoria and the Emperor Napoleon, is a glory to be shared between France and England, and you wish to know how much approval I feel I can give to this English and French victory.

Since you wish to know my opinion, here it is:

There was, in a corner of the world, a wonder of the world; this wonder was called the Summer Palace. Art has two principles, the Idea, which produces European art, and the Chimera, which produces oriental art. The Summer Palace was to chimerical art what the Parthenon is to ideal art. All that can be begotten of the imagination of an almost extra-human people was there. It was not a single, unique work like the Parthenon. It was a kind of enormous model of the chimera, if the chimera can have a model. Imagine some inexpressible construction, something like a lunar building, and you will have the Summer Palace. Build a dream with marble, jade, bronze and porcelain, frame it with cedar wood, cover it with precious stones, drape it with silk, make it here a sanctuary, there a harem, elsewhere a citadel, put gods there, and monsters, varnish it, enamel it, gild it, paint it, have architects who are poets build the thousand and one dreams of the thousand and one nights, add gardens, basins, gushing water and foam, swans, ibis, peacocks, suppose in a word a sort of dazzling cavern of human fantasy with the face of a temple and palace, such was this building. The slow work of generations had been necessary to create it. This edifice, as enormous as a city, had been built by the centuries, for whom? For the peoples. For the work of time belongs to man. Artists, poets and philosophers knew the Summer Palace; Voltaire talks of it. People spoke of the Parthenon in Greece, the pyramids in Egypt, the Coliseum in Rome, Notre-Dame in Paris, the Summer Palace in the Orient. If people did not see it they imagined it. It was a kind of tremendous unknown masterpiece, glimpsed from the distance in a kind of twilight, like a silhouette of the civilization of Asia on the horizon of the civilization of Europe.

This wonder has disappeared.

One day two bandits entered the Summer Palace. One plundered, the other burned. Victory can be a thieving woman, or so it seems. The devastation of the Summer Palace was accomplished by the two victors acting jointly. Mixed up in all this is the name of Elgin, which inevitably calls to mind the Parthenon. What was done to the Parthenon was done to the Summer Palace, more thoroughly and better, so that nothing of it should be left. All the treasures of all our cathedrals put together could not equal this formidable and splendid museum of the Orient. It contained not only masterpieces of art, but masses of jewelry. What a great exploit, what a windfall! One of the two victors filled his pockets; when the other saw this he filled his coffers. And back they came to Europe, arm in arm, laughing away. Such is the story of the two bandits.

We Europeans are the civilized ones, and for us the Chinese are the barbarians. This is what civilization has done to barbarism.

Before history, one of the two bandits will be called France; the other will be called England. But I protest, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity! the crimes of those who lead are not the fault of those who are led; Governments are sometimes bandits, peoples never.

The French empire has pocketed half of this victory, and today with a kind of proprietorial naivety it displays the splendid bric-a-brac of the Summer Palace. I hope that a day will come when France, delivered and cleansed, will return this booty to despoiled China.

Meanwhile, there is a theft and two thieves.

I take note.

This, Sir, is how much approval I give to the China expedition.”

25 November, 1861

You ask my opinion, Sir, about the China expedition. You consider this expedition to be honourable and glorious, and you have the kindness to attach some consideration to my feelings; according to you, the China expedition, carried out jointly under the flags of Queen Victoria and the Emperor Napoleon, is a glory to be shared between France and England, and you wish to know how much approval I feel I can give to this English and French victory.

Since you wish to know my opinion, here it is:

There was, in a corner of the world, a wonder of the world; this wonder was called the Summer Palace. Art has two principles, the Idea, which produces European art, and the Chimera, which produces oriental art. The Summer Palace was to chimerical art what the Parthenon is to ideal art. All that can be begotten of the imagination of an almost extra-human people was there. It was not a single, unique work like the Parthenon. It was a kind of enormous model of the chimera, if the chimera can have a model. Imagine some inexpressible construction, something like a lunar building, and you will have the Summer Palace. Build a dream with marble, jade, bronze and porcelain, frame it with cedar wood, cover it with precious stones, drape it with silk, make it here a sanctuary, there a harem, elsewhere a citadel, put gods there, and monsters, varnish it, enamel it, gild it, paint it, have architects who are poets build the thousand and one dreams of the thousand and one nights, add gardens, basins, gushing water and foam, swans, ibis, peacocks, suppose in a word a sort of dazzling cavern of human fantasy with the face of a temple and palace, such was this building. The slow work of generations had been necessary to create it. This edifice, as enormous as a city, had been built by the centuries, for whom? For the peoples. For the work of time belongs to man. Artists, poets and philosophers knew the Summer Palace; Voltaire talks of it. People spoke of the Parthenon in Greece, the pyramids in Egypt, the Coliseum in Rome, Notre-Dame in Paris, the Summer Palace in the Orient. If people did not see it they imagined it. It was a kind of tremendous unknown masterpiece, glimpsed from the distance in a kind of twilight, like a silhouette of the civilization of Asia on the horizon of the civilization of Europe.

This wonder has disappeared.

One day two bandits entered the Summer Palace. One plundered, the other burned. Victory can be a thieving woman, or so it seems. The devastation of the Summer Palace was accomplished by the two victors acting jointly. Mixed up in all this is the name of Elgin, which inevitably calls to mind the Parthenon. What was done to the Parthenon was done to the Summer Palace, more thoroughly and better, so that nothing of it should be left. All the treasures of all our cathedrals put together could not equal this formidable and splendid museum of the Orient. It contained not only masterpieces of art, but masses of jewelry. What a great exploit, what a windfall! One of the two victors filled his pockets; when the other saw this he filled his coffers. And back they came to Europe, arm in arm, laughing away. Such is the story of the two bandits.

We Europeans are the civilized ones, and for us the Chinese are the barbarians. This is what civilization has done to barbarism.

Before history, one of the two bandits will be called France; the other will be called England. But I protest, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity! the crimes of those who lead are not the fault of those who are led; Governments are sometimes bandits, peoples never.

The French empire has pocketed half of this victory, and today with a kind of proprietorial naivety it displays the splendid bric-a-brac of the Summer Palace. I hope that a day will come when France, delivered and cleansed, will return this booty to despoiled China.

Meanwhile, there is a theft and two thieves.

I take note.

This, Sir, is how much approval I give to the China expedition.”

The sacking of the Yuanming Yuan

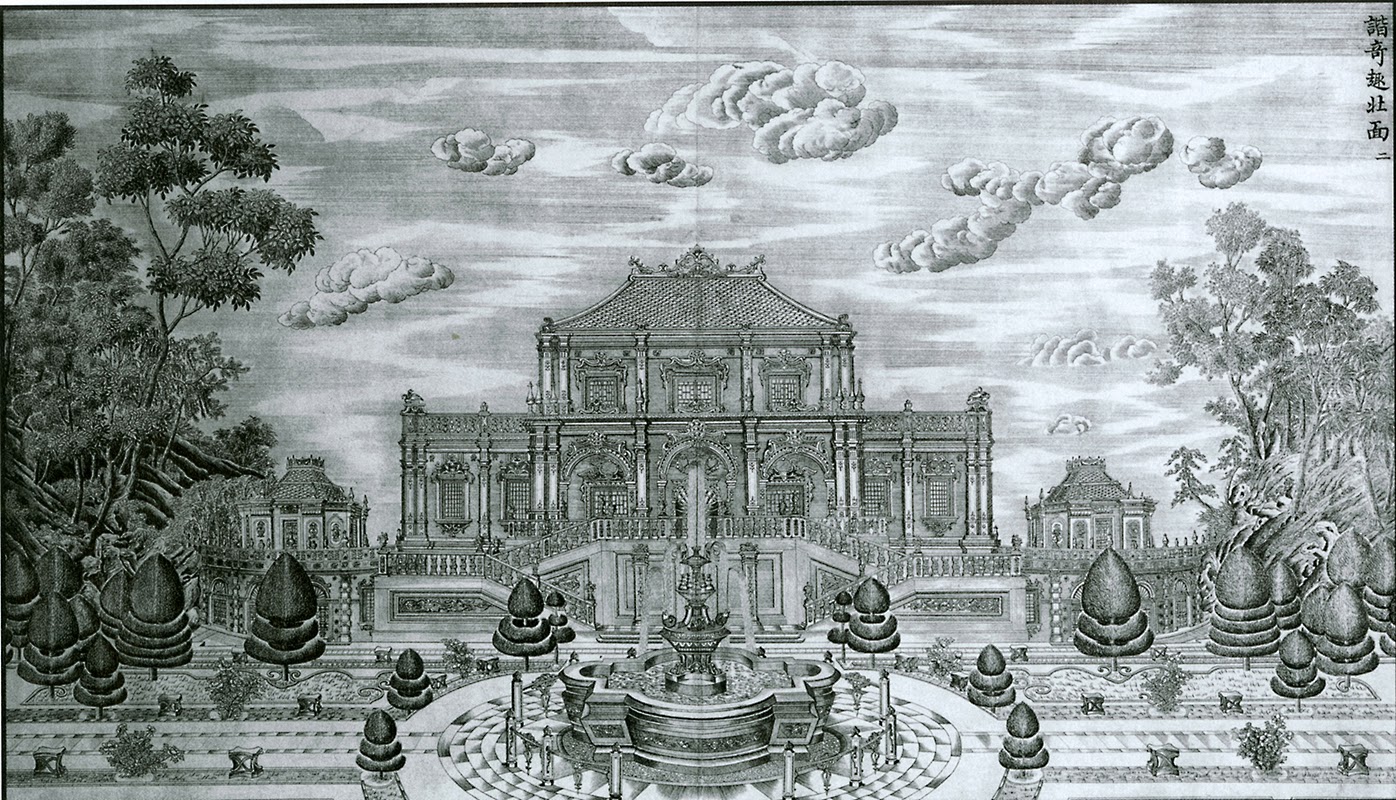

The earliest known photographs of the ruins of the European section of the Yuanming Yuan were taken by a young German clerk, Ernst Ohlmer, in 1873, just 13 years after the looting and destruction of the site. Although the buildings are damaged and the grounds overgrown with weeds, the basic architecture remains recognizable. This depicts the north side of the Xieqiqu (Palace of the Delights of Harmony), one of the main palaces. Beijing, 1873 - ©Ernst Ohlmer

- Garden of Perfect Brightness, today known as the Summer Palace

- Elegant Spring Garden (Qǐchūn Yuán)

- Garden of Eternal Spring (Changchun Yuan), to the north of which was standing the Xiyang Lou(Western mansion(s)) complex, 18th century European-style palaces, fountains and waterworks, and formal gardens designed by the Italian-French Jesuits Giuseppe Castiglione and Michel Benoist, who were employed by the Qianlong emperor to satisfy his taste for exotic buildings and objects.