历史真相

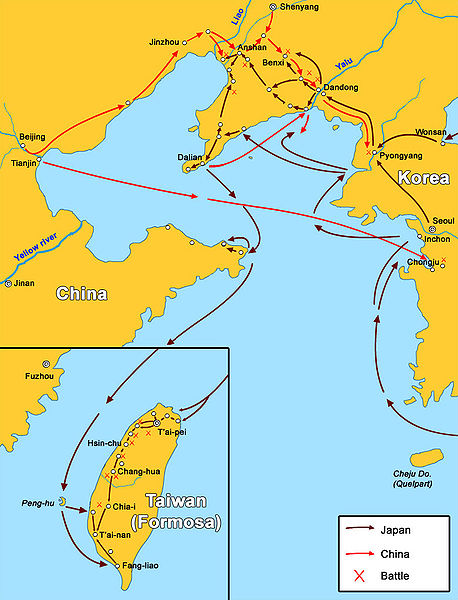

古今中外历史政治甲午战争(又称中日甲午战争、第一次中日战争;日称日清战争)是清朝和日本之间为争夺朝鲜半岛控制权而爆发的一场战争。由于发生年为1894年即清光绪二十年干支为甲午,史称“甲午战争”。

日本旗舰松岛号。

日期: 1894年8月1日 - 1895年4月17日

地点: 朝鲜半岛、中国东北

结果: 日本胜利

起因:

领土变更: 日本控制朝鲜半岛

中国割让台湾、澎湖及辽东半岛给日本

| 参战方 | |

|---|---|

| 指挥官 | |

| 兵力 | |

| 630,000 北洋军 北洋舰队 | 240,000 日本军 日本帝国海军 |

| 伤亡 | |

| 35,000人死亡或受伤 | 13,823人死亡 3,973受伤 |

起因 沙俄在中国东北与朝鲜半岛势力的扩张使日本担心在辽东半岛与朝鲜的霸权。在1875年,日本与朝鲜签署了不平等《江华条约》,使朝鲜给与日本贸易特权与互相承认自主独立国家。此条约在朝鲜造成了保守党与维新派的斗争。保守党想维持“事大交小”传统的外交方式,维新派想因此脱离于清朝的册封关系,与西方国家结交来发展朝鲜。但清朝仍然控制了李朝朝廷保守的官员与贵族。 在1884年,朝鲜维新派试图推翻李朝。在朝鲜的邀请下,袁世凯带领清军开入汉城,并且杀了几个日本人。中日天津会议专条避免了两国的战争,日本与清朝同时从朝鲜撤兵,和约定两国或一国要派兵,应先互行文知照。 1894年春,朝鲜爆发“东学党”农民起义,朝鲜政府于6月3日请求清政府派兵协助镇压。

交战双方

清朝

北洋海军自1888年正式建军后,配置有主力舰定远号及镇远号,各有12寸巨炮4尊,航速分别为14.5节及15.4节。甲午战争前夕,英国的阿摩士庄(Armstrong)船厂向李鸿章推销世界航速最快,达23节的四千吨巡洋舰。这艘舰最后被日本买下了,也就是后来的吉野号,在甲午一战发挥极大战力。1894年5月下旬李鸿章校阅北洋海军,奏称:“北洋各舰及广东三船沿途行驶操演,船阵整齐变化,雁行鱼贯,操纵自如……以鱼雷六艇试演袭营阵法,攻守多方,备极奇奥。”“于驶行之际,击穹远之靶,发速中多。经远一船,发十六炮,中至十五。广东三船,中靶亦在七成以上。”“夜间合操,水师全军万炮并发,起止如一。英、法、俄、日本各国,均以兵船来观,称为节制精严。”战争前夕,北洋舰队的大沽、威海卫(今山东威海)和旅顺(今属辽宁大连)三大基地建成,英国观察员看完北洋舰队的操演后上书海军部,也认为北洋舰队的战力不容小觑。

但是后期因为李鸿章解雇了当时训练海军的英国人琅威理,引致北洋舰队军纪出现问题,“有某西人偶登其船,见海军提督正与巡兵团同坐斗竹牌也。”“每北洋封冻,海军岁例巡南洋,率淫赌于香港、上海,识者早忧之”。1888年后因为军费被挪用去修建颐和园,所以北洋海军未添船购炮,“从前拨定北洋经费号称二百万两,近年停解者多,岁仅收五六十万。”[1]“中国水雷船排列海边,无人掌管,外则铁锈堆积,内则秽污狼藉,业已无可驶用。”至于领导丁汝昌“孤寄群闽人之上,遂为闽党所制,威令不行”。刘步蟾则被人们称为“实际上之提督者”。

日本

1882年,日本海军还只是鱼雷艇和二千吨以下的近海铁甲舰为主,无大型铁甲巡洋舰。1885年,日本提出十年的扩军计划,意图超过北洋海军。1886年,法国海军工程师白劳易(Louis-?mile Bertin)受雇建造4700吨级大型铁甲巡洋舰“松岛号”和“厳岛号”。1890年时,中国北洋舰队的总排水量为27000吨,而日本海军的总排水量在17000吨以上。日本以国家财政收入的60%来发展海、陆军,当时日本政府的年度财政收入只有八千万日元。1893年起,明治天皇又决定每年从自己的宫廷经费中拨出三十万日圆,再从官员的薪水里取十分之一,补充造船费用。到了1894年甲午战争时,日本海军舰队总排水量为72000吨,并且多有配置速射炮的新式舰艇。相反,北洋舰队自1888年正式成立后,再未添加任何船只。1891年后,又停购枪炮弹药,后来海军军费挪用修了慈禧的颐和园。

战前日本实际动员兵力达240616人,174017人有参战经验,海军拥有军舰32艘、鱼雷艇24艘,排水量72000吨,超越北洋水师。日本对清廷改革后的实力仍有顾忌,对于北洋水师不敢轻敌,1880年日本参谋本部长山县有朋的调查报告中指出,大清帝国平时可征兵425万,战时可达850万人之多,“邻邦之兵备愈强,则本邦之兵备亦更不可懈”。

过程

甲午战争始于1894年7月25日的丰岛海战,至8月1日清朝政府对日宣战和日本明治天皇发布宣战诏书,1895年4月17日以签署《马关条约》而告结束。整个战争持续近9个月,依据战场转换及双方作战态势的变化,大致分为三个阶段。

第一阶段

第一阶段,从1894年7月25日到9月17日。战争分陆战与海战双向进行,陆战主要是在朝鲜半岛上的平壤之战,海战主要是黄海海战。

陆面战斗在三个战场同时展开:大同江南岸战场、玄武门外战场、城西南战场。当时驻守平壤的清军三十五营共一万七千人,日军也有一万六千多人,双方战力相埒。日军第九混成旅团首先向大同江南岸清军发起进攻,太原镇总兵马玉崑奋勇抗击,日军无功而返。同时日海军联合舰队进入黄海合击北洋水师舰队,这是人类历史上第一次的大规模现代海战,至今仍是中国历史上唯一的一次。激战5小时后,北洋舰队损失巡洋舰5艘,受伤4艘,日舰仅伤5艘。9月15日,日军分三路总攻平壤,战斗至为激烈,高州镇总兵左宝贵不幸中炮牺牲,随后玄武门失守,叶志超下令彻退,六日内狂泄五百余里,26日清军直抵鸭绿江以北的中国境内。日本联合舰队达到了控制黄海制海权的目的。

第二阶段

第二阶段,从1894年9月17日到11月22日。战场位于辽东半岛,以陆战为主。9月25日,日军在鸭绿江上搭浮桥抢渡成功,向虎山清军阵地发起进攻。清军守将马金叙、聂士成被迫撤出阵地。日军陷虎山。其他清军各部不战而逃,山县有朋即将第一军司令部移于虎山。26日,日军占领了九连城和安东县(今丹东),同日日军在旅顺花园口登陆,10月9日,攻占金州,10日陷大连湾,至此清军在鸭绿江防线全线崩溃。25日旅顺陷落,日军进行大屠杀。

第三阶段

第三阶段,从1894年11月22日到1895年4月17日,有威海卫之战和辽东之战。1895年1月20日,日本第二军共两万五千人,在日舰掩护下开始在荣成龙须岛登陆。30日日军集中兵力进攻威海卫南帮炮台。营官周家恩壮烈牺牲,炮台终被日军攻占。2月3日日军陷威海卫城,刘公岛成为孤岛,日本联合舰队司令伊东祐亨曾致书丁汝昌劝降。10日,定远号弹药告罄,刘步蟾下令将舰炸沉,随后刘步蟾自杀。11日,丁汝昌自杀。17日,日军在刘公岛登陆,北洋舰队全军覆没。北线日军在海军配合,一路攻陷菲尼克斯、海城、营口、田庄台。清廷求和心切,派李鸿章为全权大臣,赴日议和。4月17日签定《中日马关条约》,甲午战争结束。

分析

丰岛海战和黄海海战两次遭遇日本联合舰队,北洋舰队被击沉多艘大型舰艇,但未能击沉一艘日舰,也无发射鱼雷打击日舰的战绩。据查是丁汝昌“只识弓马”,一干管带也全用错了炮弹,不用海战时的开花爆破弹,用了穿甲弹甚至训练弹。丰岛海战中,日本吉野号被一枚济远舰150毫米口径火炮击中右舷,击毁舢板数只,穿透钢甲,击坏发电机,坠入机舱的防护钢板上,然后又转入机舱里。可是由于弹头里面未装炸药,所以击中而不爆炸,使吉野侥幸免于报废。黄海海战中,北洋海军发射的炮弹有的弹药中“实有泥沙”,有的引信中“仅实煤灰,故弹中敌船而不能裂”。当时在镇远舰上协助作战的美国人麦吉芬(Paul W. Bamford,1860-1897,美国安纳波利斯海军学院毕业)认为,吉野号能逃脱,是因为所中炮弹只是固体弹头的穿甲弹[2]。据统计,在定远和镇远发射的197枚12英寸(305毫米)口径炮弹中,半数是固体弹头的穿甲弹,而不是爆破弹头的开花弹[3]。在直隶候补道徐建寅的《上督办军务处查验北洋海军禀》之后附有《北洋海军各员优劣单》、《北洋海军各船大炮及存船各种弹子数目清折》、《北洋海军存库备用各种大炮弹子数目清折》中统计,参加过黄海大战的定远、镇远、靖远、来远、济远、广丙7舰的存舰存库炮弹,仅开花爆破弹一项即达3431枚。其中,供305毫米口径炮使用的炮弹有403枚,210毫米口径炮弹952枚,150毫米口径炮弹1237枚,120毫米口径炮弹362枚,6英寸口径炮弹477枚。黄海海战后,又拨给北洋海军360枚开花弹,其中305毫米口径炮弹160枚,210、150毫米口径炮弹各100枚。在3431枚开花弹中,有3071枚早在黄海海战前就已拨给北洋海军。苏小东《甲午年徐建寅奉旨查验北洋海军考察》猜测:“至于这批开花弹为什么没有用于黄海海战,惟一的解释就是它们当时根本不在舰上,而是一直被存放在旅顺、威海基地的弹药库里。由此可见,造成北洋海军在黄海海战中弹药不足的责任不在机器局,也不在军械局,而在北洋海军提督丁汝昌身上。”在中日双方开战后,丁汝昌执行李鸿章“保船制敌”的方针,消极避战,“仍心存侥幸,出海护航时竟然连弹药都没有带足,致使北洋海军在弹药不足的情况下与日本舰队进行了一场长达5个小时的海上会战,结果极大地影响了战斗力的发挥,也加重了损失的程度”。

北洋水师与联合舰队进攻火力对比如下,北洋水师略逊一筹,但重炮占优势,如果炮弹选择得当可以重创日舰。就防守能力而言,北洋水师略胜一筹,定远号、镇远号的护甲厚14寸,即使是经远号、来远号的护甲厚也达9.5寸。海战结束后,定远号、镇远号的护甲无一处被击穿。就平均船速而言,北洋水师较慢,为15.5节(即海里/小时),联合舰队的本队15.6节也不快,但包括吉野号在内的第一游击编队为19.4节,大大高于北洋水师。

| 军舰总数 | 30厘米重炮 | 20-30厘米大炮 | 15-20厘米轻炮 | 15厘米速射炮 | 舰艇排水量 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 北洋舰队 | 12 | 8 | 16 | 149 | 0 | 3.5万吨 |

| 日本舰队 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 160 | 97 | 4.1万吨 |

此外,北洋海军各主力舰都设有鱼雷管3-4具,但是,在黄海海战中,并没有对日舰实施鱼雷攻击。丁汝昌在汇报战况时,也只字未提已方发射鱼雷,而只说日舰对经远和致远发动鱼雷攻击。购舰时就配备好的大批鱼雷在战争爆发后可能也和大批开花弹不在舰上一样,被放在基地的仓库里派不上用场。另外,各舰炮弹数量也未带足,海战时炮弹在五个小时内用尽。战至最后,未受大伤仍可继续打击日舰的7000吨巨舰定远、镇远弹药告竭,分别仅余12英寸口径钢铁弹3发、2发,不得不退出战场。

如果考虑到上面所提到的库存弹药可能是因为无法使用而搁置的,则丁汝昌责任就较小,但李鸿章的责任并无减轻。担任天津军械局总办、负责军需供应的张士珩是李鸿章的外甥,供给海军的弹药不合格。梁启超评论说:“枪或苦窳,弹或赝物,枪不对弹,药不随械,谓从前管军械之人廉明,谁能信之?”另外,丁汝昌战前提出在主要舰船上配置速射炮以抵消日舰速射炮的优势,需银六十万两。李鸿章声称无款。北洋舰队在黄海海战中战败,他才上奏前筹海军巨款分储各处情况:“汇丰银行存银一百零七万两千九百两;德华银行存银四十四万两;怡和洋行存银五十五万九千六百两 ;开平矿务局领存五十二万七千五百两;总计二百六十万两。”

结果及影响

甲午战争对远东战略格局产生了深刻的影响,清朝军队撤出朝鲜半岛,清朝割让台湾、澎湖及其附属岛屿予日本,向日本开放多个中国内陆的港口城市,日本又获2.3亿两白银的战争赔款(其中三千万两为清朝换回辽东半岛的费用),经济迅速发展并进一步扩军备战,开始成为远东的主要战争策源地,同时日本崛起改变了远东地区由英国和俄国对立和争霸的原有格局,导致数年后的英日联盟和日俄开战。而中国在甲午战争中的失败(北洋水师的覆灭)标志着洋务运动的失败,大清帝国的国际地位自此一落千丈,再次成为列强鲸吞蚕食的对象。清朝国内的改革派对自身的弱点有了更深的认识,准备积极进行进一步的改革﹝即戊戌变法﹞。

主要战役

丰岛海战

黄海海战

平壤之战

旅顺大屠杀

威海卫海战

乙未战争

| First Sino-Japanese War, major battles and troop movements | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 630,000 men Beiyang Army, Beiyang Fleet | 240,000 men | ||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| 35,000 dead or wounded | 13,823 dead, 3,973 wounded | ||||||||

| First Sino-Japanese War |

|---|

| Pungdo (naval) – Seonghwan –Pyongyang – Yalu River (naval) – Jiuliangcheng (Yalu) – Lushunkou – Weihaiwei – Yingkou |

The First Sino-Japanese War (Traditional Chinese: 中日甲午戰爭; Pinyin: Zhōngrì Jiǎwǔ Zhànzhēng; Japanese: 日清戦争 Romaji: Nisshin Sensō) (1 August 1894–17 April 1895) was a war fought between Qing Dynasty China and Meiji Japan over the control of Korea. The Sino-Japanese War would come to symbolize the degeneration and enfeeblement of the Qing Dynasty and demonstrate how successful modernization had been in Japan since the Meiji Restoration as compared with the Self-Strengthening Movement in China. The principal results were a shift in regional dominance in Asia from China to Japan and a fatal blow to the Qing Dynasty and the Chinese classical tradition. These trends would result later in the 1911 Revolution.

Background and causes

Prologue

Japan long had a desire to expand its realm to the mainland of east Asia. During Toyotomi Hideyoshi's rule in the late 16th century, Japan had invaded Korea (1592-1598) but after initial successes had failed to achieve complete victory and control of Korea.

After two centuries, the seclusion policy, or Sakoku, under the shoguns of the Edo period came to an end when the country was forced open to trade by American intervention in 1854. The years following the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the fall of the Shogunate had seen Japan transform itself from a feudal and comparatively backward society to a modern industrial state. The Japanese had sent delegations and students around the world in order to learn and assimilate western arts and sciences, this was done to prevent Japan falling under foreign domination and also enable Japan to compete equally with the Western powers.

Conflict over Korea

As a newly emergent country, Japan turned its attention towards Korea. It was vital for Japan, in order to protect its own interests and security, to either annex Korea before it fell prey (or was annexed) to another power or to insure its effective independence by opening its resources and reforming its administration. As one Japanese statesman put it, "an arrow pointed at the heart of Japan". Japan felt that another power having a military presence on the Korean peninsula would have been detrimental to Japanese national security, and so Japan resolved to end the centuries-old Chinese suzerainty over Korea. Moreover, Japan realized that Korea’s coal and iron ore deposits would benefit Japan's increasingly-expanding industrial base.

Korea had traditionally been a tributary state and continued to be so under the influence of China's Qing dynasty, which exerted large influence over the conservative Korean officials gathered around the royal family of the Joseon Dynasty. Opinion in Korea itself was split; conservatives wanted to retain the traditional subservient relationship with China, while reformists wanted to establish closer ties with Japan and western nations. After two Opium Wars and the Sino-French War, China had become weak and was unable to resist western intervention and encroachment (see Unequal Treaties). Japan saw this as an opportunity to replace Chinese influence in Korea with its own.

On February 26, 1876, after certain incidents and confrontations involving Korean isolationists and the Japanese, Japan imposed the Treaty of Ganghwa on Korea, forcing Korea to open itself to Japanese and foreign trade and to proclaim its independence from China in its foreign relations.

In 1884 a group of pro-Japanese reformers briefly overthrow the pro-Chinese conservative Korean government in a bloody coup d'état. However, the pro-Chinese faction, with assistance from Chinese troops under General Yuan Shikai, succeeded in regaining control with an equally bloody counter-coup which resulted not only in the deaths of a number of the reformers, but also in the burning of the Japanese legation and the deaths of several legation guards and citizens in the process. This caused an incident between Japan and China, but was eventually settled by the Sino-Japanese Convention of Tientsin of 1885 in which the two sides agreed to (a) pull their expeditionary forces out of Korea simultaneously; (b) not send military instructors for the training of the Korean military; and (c) notify the other side beforehand should one decide to send troops to Korea. The Japanese, however, were frustrated by repeated Chinese attempts to undermine their influence in Korea.

Status of combatants

Japan

Japan's reforms under the Meiji emperor gave significant priority to naval construction and the creation of an effective modern national army and navy. Japan sent numerous military officials abroad for training, and evaluation of the relative strengths and tactics of European armies and navies.

The Imperial Japanese Navy

| Major Combatants |

|---|

| Protected Cruisers |

| Matsushima (flagship) |

| Itsukushima |

| Hashidate |

| Naniwa |

| Takachiho |

| Yaeyama |

| Akitsushima |

| Yoshino |

| Izumi |

| Cruisers |

| Chiyoda |

| Armored Corvettes |

| Hiei |

| Kongō |

| Ironclad Warship |

| Fusō |

The Imperial Japanese Navy was modeled after the Royal Navy, at the time the foremost naval power in the world. British advisors were sent to Japan to train, advise and educate the naval establishment, while students were in turn sent to Great Britain in order to study and observe the Royal Navy. Through drilling and tuition by Royal Navy instructors, Japan was able to possess a navy expertly skilled in the arts of gunnery and seamanship.

At the start of hostilities the Imperial Japanese Navy contained a fleet (although lacking in battleships) of 12 modern warships (Izumi being added during the war), one frigate (Takao), 22 torpedo boats, and numerous auxiliary/armed merchant cruisers and converted liners.

Japan did not yet have the resources to acquire battleships and so planned to employ the "Jeune Ecole" ("young school") doctrine which favoured small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, against bigger units.

Many of Japan’s major warships were built in British and French shipyards (eight British, three French, and two Japanese-built) and 16 of the torpedo boats were known to have been built in France and assembled in Japan.

The Imperial Japanese Army

The Meiji era government at first modeled the army on the French Army—French advisers had been sent to Japan with the two military missions (in 1872-1880 and 1884; these were the second and third missions respectively, the first had been under the shogunate). Nationwide conscription was enforced in 1873 and a western-style conscript army was established; military schools and arsenals were also built.

In 1886 Japan turned towards the German Army, specifically the Prussian model as the basis for its army. Its doctrines, military system and organisation were studied in detail and adopted by the IJA. In 1885, Jakob Meckel, a German adviser implemented new measures such the reorganization of the command structure of the army into divisions and regiments; the strengthening of army logistics, transportation, and structures (thereby increasing mobility); and the establishment of artillery and engineering regiments as independent commands.

By the 1890s, Japan had at its disposal a modern, professionally trained western-style army which was relatively well equipped and supplied. Its officers had studied abroad and were well educated in the latest tactics and strategy.

By the start of the war, the Imperial Japanese Army could field a total force of 120,000 men in two armies and five divisions.

| Imperial Japanese Army Composition 1894-1895 |

| 1st Japanese Army |

|---|

| 3rd Provincial Division (Nagoya) |

| 5th Provincial Division (Hiroshima) |

| 2nd Japanese Army |

| 1st Provincial Division (Tokyo) |

| 2nd Provincial Division (Sendai) |

| 6th Provincial Division (Kumamoto) |

| In Reserve |

| 4th Provincial Division (Osaka) |

| Invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) |

| Imperial Guards Division |

China

Although the Beiyang Force was the best equipped and symbolized the new modern Chinese military, morale and corruption were serious problems; politicians systematically embezzled funds, even during the war. Logistics were a huge problem, as construction of railroads in Manchuria had been discouraged. The morale of the Chinese armies was generally very low due to lack of pay and prestige, use of opium, and poor leadership which contributed to some rather ignominious withdrawals such as the abandonment of the very well fortified and defensible Weihaiwei.

Beiyang Army

Qing Dynasty China did not have a national army, but following the Taiping Rebellion, had been segregated into separate Manchu, Mongol, Hui (Muslim) and Han Chinese armies, which were further divided into largely independent regional commands. During the war, most of the fighting was done by the Beiyang Army and Beiyang Fleet while pleas calling for help to other Chinese armies and navies were completely ignored due to regional rivalry.

Beiyang Fleet

| Beiyang Fleet | Major Combatants |

|---|---|

| Ironclad Battleships | Dingyuan (flagship), Zhenyuan |

| Armoured Cruisers | King Yuen, Lai Yuen |

| Protected Cruisers | Chih Yuen, Ching Yuen |

| Cruisers | Torpedo Cruisers - Tsi Yuen, Kuang Ping/Kwang Ping | Chaoyong, Yangwei |

| Coastal warship | Ping Yuen |

| Corvette | Kwan Chia |

13 or so Torpedo boats, numerous Gun boats and chartered merchant vessels

Early stages of the war

In 1893 a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary, Kim Ok-kyun, was assassinated in Shanghai, allegedly by agents of Yuan Shikai. His body was then put aboard a Chinese warship and sent back to Korea, where it was supposedly quartered and displayed as a warning to other rebels. The Japanese government took this as a direct affront. The situation became increasingly tense later in the year when the Chinese government, at the request of the Korean Emperor, sent troops to aid in suppressing the Tonghak Rebellion. The Chinese government informed the Japanese government of its decision to send troops to the Korean peninsula in accordance with the Convention of Tientsin, and sent General Yuan Shikai as its plenipotentiary at the head of 2,800 troops. The Japanese countered that they consider this action to be a violation of the Convention, and sent their own expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) of 8,000 troops to Korea. The Japanese force subsequently seized the emperor, occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul by 8 June 1894, and replaced the existing government with the members from the pro-Japanese faction. Though Chinese troops were already leaving Korea, finding themselves unwanted there, the new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel the Chinese troops forcefully, while Japan shipped more troops to Korea. The legitimacy of the new government was rejected by China, and the stage was thus set for conflict.

Events during the war

War between China and Japan was officially declared on 1 August 1894, though some combat had already taken place. The Imperial Japanese Army attacked and defeated the poorly-prepared Chinese Beiyang Army, at the Battle of Pyongyang on 16 September 1894, and quickly pushed north into Manchuria. The Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed 8 out of 10 warships of the Chinese Beiyang Fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River on 17 September 1894. The Chinese fleet subsequently retreated behind the Weihaiwei fortifications. However, they were then surprised by Japanese ground forces, who outflanked the harbor's defenses.

By 21 November 1894, the Japanese had taken the city of Lüshunkou (later known as Port Arthur). The Japanese army allegedly massacred thousands of the city's civilian Chinese inhabitants, in an event that came to be called the Port Arthur Massacre.

After Weihaiwei's fall on 2 February 1895 and an easing of harsh winter conditions, Japanese troops pressed further into southern Manchuria and northern China. By March 1895 the Japanese had fortified posts that commanded the sea approaches to Beijing.

End of the war

The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on 17 April 1895. China recognised the total independence of Korea, ceded the Liaodong Peninsula (In present-day south of Liaoning Province), Taiwan/Formosa and the Pescadores Islands to Japan "in perpetuity". Additionally, China was to pay Japan 200 million Kuping taels as reparation. China also signed a commercial treaty permitting Japanese ships to operate on the Yangtze River, to operate manufacturing factories in treaty ports and to open four more ports to foreign trade. The Triple Intervention however forced Japan to give up the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for another 450 million Kuping taels.

Aftermath

The Japanese success of the war was the result of the modernisation and industrialisation embarked on two decades earlier. The war demonstrated the superiority of Japanese tactics and training as a result of the adoption of a western style military. The Imperial Japanese Army and Navy were able to inflict a string of defeats on the Chinese through foresight, endurance, strategy and power of organization. Japanese prestige rose in the eyes of the world. The victory established Japan as a power (if not a great power) on equal terms with the west and as the dominant power in Asia.

The war for China revealed the failure of its government, its policies, the corruption of the administration system and the decaying state of the Qing dynasty (something that had been recognised for decades). Anti-foreign sentiment and agitation grew and would later accumulate in the form of the Boxer Rebellion five years later. Throughout the 19th century the Qing dynasty was unable to prevent foreign encroachment—this together with calls for reform and the Boxer Rebellion would be the key factors that would lead to 1911 revolution and the downfall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.

Although Japan had achieved what it had set out to accomplish, namely to end Chinese influence over Korea, Japan reluctantly had been forced to relinquished the Liaodong Peninsula (Port Arthur) in exchange for an increased financial indemnity. The European powers (Russia especially) while having no objection to the other clauses of the treaty, did feel that Japan should not gain Port Arthur, for they had their own ambitions in that part of the world. Russia persuaded Germany and France to join her in applying diplomatic pressure on the Japanese, resulting in the Triple Intervention of 23 April 1895.

In 1898 Russia signed a 25-year lease on Liaodong Peninsula and preceded to set a naval station at Port Arthur. Although this infuriated the Japanese, they were more concerned with Russian encroachment towards Korea than in Manchuria. Other powers, such as France, Germany, and Great Britain, took advantage of the situation in China and gained port and trade concessions at the expense of the decaying Qing Empire. Tsingtao and Kiaochow was acquired by Germany, Kwang-Chou-Wan by France, and Weihaiwei by Great Britain.

Tensions between Russia and Japan would increase in the years after the First Sino-Japanese war. During the Boxer Rebellion an eight member international force was sent to suppress and quell the uprising; Russia sent troops into Manchuria as part of this force. After the suppression of the Boxers the Russian Government agreed to vacate the area. However by 1903 it had actually increased the number of its forces in Manchuria. Negotiations between the two nations (1901–1904) to establish mutual recognition of respective spheres of influence (Russia over Manchuria and Japan over Korea) were repeatedly and intentionally stalled by the Russians. They felt that they were strong and confident enough not to accept any compromise and believed Japan would not dare go to war against a European power. Russia also had intentions to use Manchuria as a springboard for further expansion of its interests in the Far East.

In 1902, Japan formed an alliance with Britain the terms of which stated that if Japan went to war in the Far East, and that a third power entered the fight against Japan, then Britain would come to the aid of the Japanese. This was a check to prevent either Germany or France from intervening militarily in any future war with Russia. British reasons for joining the alliance were also to check the spread of Russian expansion into the Pacific, thereby threatening British interests.

Increasing tensions between Japan and Russia as a result of Russia's unwillingness to enter into a compromise and the prospect of Korea falling under Russia's domination, therefore coming into conflict with and undermining Japan's interests, compelled Japan to take action. This would be the deciding factor and catalyst that would lead to the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05.

War Reparations

After the war, according to the Chinese scholar, Jin Xide, the Qing government paid a total of 340,000,000 taels silver to Japan for both the reparations of war and war trophies, equivalent to (then) 510,000,000 Japanese yen, about 6.4 times the Japanese government revenue. Similarly, the Japanese scholar, Ryoko Iechika, calculated that the Qing government paid total $21,000,000 (about one third of revenue of the Qing government) in war reparations to Japan, or about 320,000,000 Japanese yen, equivalent to (then) two and half years of Japanese government revenue.

Chronicle of the war

Genesis of the war

1 June 1894 : The Tonghak Rebellion Army moves towards Seoul. The Korean government requests help from the Chinese government to suppress the rebellion force.

6 June 1894: The Chinese government informs the Japanese government under the obligation of Convention of Tientsin of its military operation. About 2,465 Chinese soldiers were transported to Korea within days.

8 June 1894: First of around 4,000 Japanese soldiers and 500 marines land at Chumlpo (Incheon) despite Korean and Chinese protests.

11 June 1894: End of Tonghak Rebellion.

13 June 1894: Japanese government telegraphs Commander of the Japanese forces in Korea, Otori Keisuke to remain in Korea for as long as possible despite the end of the rebellion.

16 June 1894: Japanese Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu meets with Wang Fengzao, Chinese ambassador to Japan, to discuss the future status of Korea. Wang states that Chinese government intends to pull out of Korea after the rebellion has been suppressed and expects Japan to do the same. However, China also appoints a resident to look after Chinese interests in Korea and to re-assert Korea’s traditional subservient status to China.

22 June 1894: Additional Japanese troops arrive in Korea.

3 July 1894: Otori proposes reforms of the Korean political system, which is rejected by the conservative pro-Chinese Korean government.

7 July 1894: Mediation between China and Japan arranged by British ambassador to China fails.

19 July 1894: Establishment of Japanese Joint Fleet, consisting of almost all vessels in the Imperial Japanese Navy, in preparation for upcoming war.

Early stage of the war on Korean soil

23 July 1894: Japanese troops enter Seoul, seize the Korean Emperor and establish a new pro-Japanese government, which terminates all Sino-Korean treaties and grants the Imperial Japanese Army the right to expel Chinese Beiyang Army troops from Korea.

25 July 1894: Naval Battle of Pungdo, offshore Asan, Korea.

29 July 1894: Battle of Seonghwan near Asan, Korea; Asan itself falls to Japan the following day.

1 Aug 1894: Formal Declaration of War.

15 September 1894: Battle of Pyongyang, northern Korea.

17 September 1894: Naval Battle of the Yalu River (1894) on border of Korea and Manchuria.

Sino-Japanese War on Chinese soil

24 October 1894: Battle of Jiuliangcheng. The Japanese First Army, under the command of Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo invades Manchuria.

21 November 1894: Battle of Lushunkou followed by Port Arthur Massacre.

10 December 1894: Kaipeng (modern Gaixian, Liaoning Province, China) falls to the Japanese 1st Army under Lieutenant General Katsura Taro.

12 February 1895: Battle of Weihaiwei, Shandong, China.

5 March 1895: Battle of Yingkou, Liaoning Province, China.

26 March 1895: Japanese forces invade and occupy the Pescadores Islands off of Taiwan without casualties.

29 March 1895: Japanese forces under Admiral Motonori Kabayama land in northern Taiwan.

17 April 1895: China signs Treaty of Shimonoseki ending the First Sino-Japanese War, granting the complete independence of Korea, ceding the Liaodong peninsula, the islands of Taiwan (Formosa), and the Pescadores Islands to Japan and paying Japan a war indemnity of 200 million Kuping taels.

| Diplomacy of the Great Powers 1871-1913 |

| Great Powers |

| British Empire | German Empire | French Third Republic | Russian Empire | Austria-Hungary | Italy |

| Treaties and agreements |

| Treaty of Frankfurt | League of the Three Emperors | Treaty of Berlin German-Austrian Alliance | Triple Alliance | Reinsurance Treaty | Franco-Russian Alliance Anglo-Japanese Alliance | Anglo-Russian Entente | Entente Cordiale | Triple Entente |

| Events |

| Russo-Turkish War | Congress of Berlin | Scramble for Africa | Fleet Acts | The Great Game First Sino-Japanese War | Fashoda Incident | Pan-Slavism | Boxer Rebellion | Boer War | Russo-Japanese War First Moroccan Crisis | Dreadnought | Agadir Crisis | Bosnian crisis | Italo-Turkish War | Balkan wars |

References

1. Chamberlin, William Henry. Japan Over Asia, 1937, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston, 395 pp.

2. Colliers (Ed.), The Russo-Japanese War, 1904, P.F. Collier & Son, New York, 129 pp.

3. Kodansha Japan An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1993, Kodansha Press, Tokyo ISBN 4-06-205938-X

4. Lone, Stewart. Japan's First Modern War: Army and Society in the Conflict with China, 1894-1895, 1994, St. Martin's Press, New York, 222 pp.

5. Paine, S.C.M. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy, 2003, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 412 pp.

6. Sedwick, F.R. (R.F.A.). The Russo-Japanese War, 1909, The Macmillan Company, NY, 192 pp.

7. Theiss, Frank. The Voyage of Forgotten Men, 1937, Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1st Ed., Indianapolis & New York, 415 pp.

8. Warner, Dennis and Peggy. The Tide At Sunrise, 1974, Charterhouse, New York, 659 pp.

9. Urdang, Laurence/Flexner, Stuart, Berg. "The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, College Edition. Random House, New York, (1969).

10.Military Heritage did an editorial on the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 (Brooke C. Stoddard, Military Heritage, December 2001, Volume 3, No. 3, p.6).