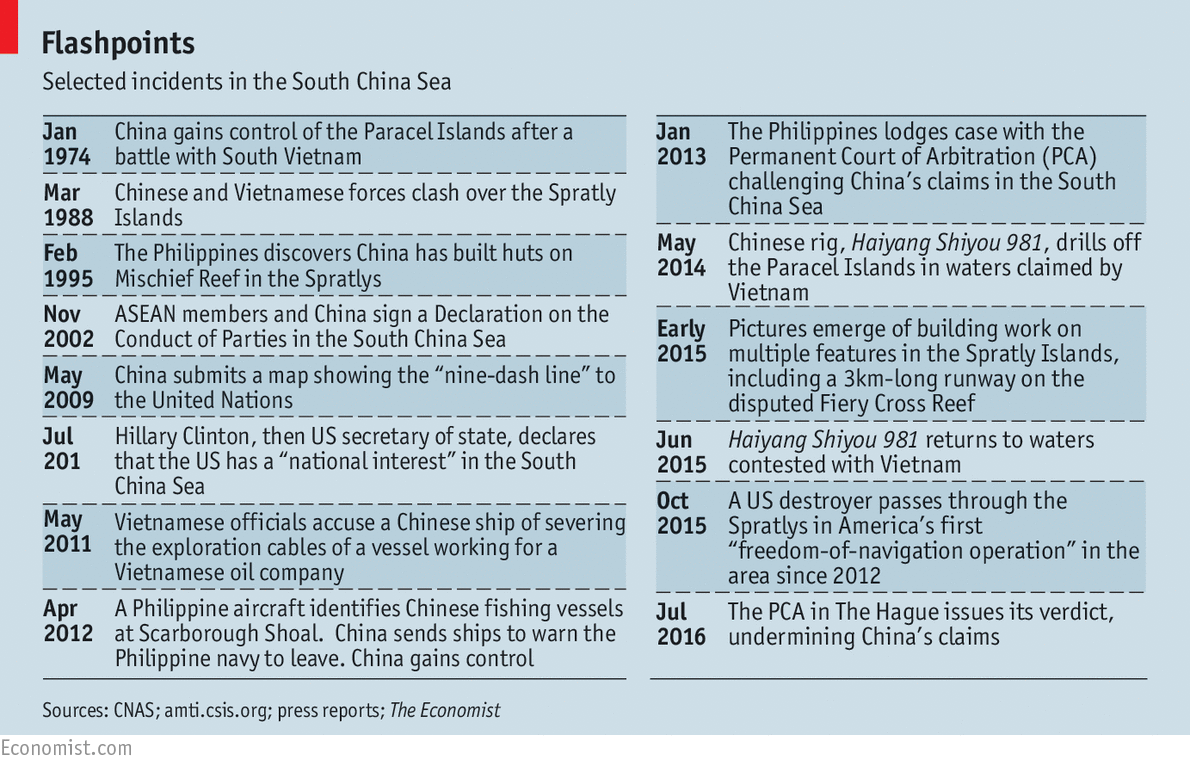

BY EJECTING its neighbours’ forces, building up its navy and constructing artificial islands, China has for years sought to assert vast and ambiguous territorial claims in the South China Sea. These alarm its neighbours and have led to military confrontations. They also challenge America’s influence in Asia. Now the Permanent Court of Arbitration, an international tribunal in The Hague, has declared China’s “historic claims” in the South China Sea invalid. It was an unexpectedly wide-ranging and clear-cut ruling, and it has enraged China. The judgment could change the politics of the South China Sea and, in the long run, force China to choose what sort of country it wants to be—one that supports rules-based global regimes, or one that challenges them in pursuit of great-power status.

The case was brought by the Philippines in 2013, after China grabbed control of a reef, called Scarborough Shoal, about 220 miles (350km) north-west of Manila. The case had wider significance, though, because of the South China Sea itself. About a third of world trade passes through its sea lanes, including most of China’s oil imports. It contains large reserves of oil and gas. But it matters above all because it is a place of multiple overlapping maritime claims and a growing military presence (Chinese troops are pictured above on one of the sea’s islands). America had two aircraft carriers in the sea lately; on the eve of the court’s ruling, China’s navy was staging a live-fire exercise there. Above all it is a region where two world-views collide. These are an American idea of rules-based international order and a Chinese one based on what it regards as “historic rights” that trump any global law.

China claims it has such rights in the South China Sea,and that they long predate the current international system. Chinese seafarers, the government says, discovered and named islands in the region centuries ago. It says the country also has ancestral fishing rights. In early July, by happy coincidence, a state television company began a mini-series about the experience of Chinese fishermen in the 1940s, reinforcing China’s view. These rights are said to exist within a “nine-dash line” (still usually called that, though Chinese maps began showing ten dashes in 2013 to bring Taiwan more clearly into the fold). It is a tongue-shaped claim that slurps more than 1,500km down from the southern coast of China and laps up almost all the South China Sea (see map)

.

The court comprehensively rejected China’s view of things, ruling that only claims consistent with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) were valid. Under UNCLOS, which came into force in 1982 and which China ratified in 1996, maritime rights derive from land, not history. Countries may claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) up to 200 nautical miles (370km) off their coasts, or around islands. Based on this, the tribunal ruled that the nine-dash line had no standing. The judges wrote that there was “no legal basis” for China to claim historic rights within it. UNCLOS, they said, took precedence.

Until now, China has not specified the exact meaning of the nine-dash line. It is not clear, for example, whether the country claims everything within the line as its sovereign possession or merely the islands and their surrounding waters. Even if the claim were confined to the islands, the ruling undermined that. The tribunal said that none of the Spratly Islands (where China’s island-building has been concentrated) count as islands in international law. Therefore, none qualifies for an EEZ.

Adding insult to injury, the court ruled that China had been building on rocks that were visible only at low tide, and hence not eligible to claim territorial waters. It said this had violated the sovereign rights of the Philippines, which has an EEZ covering them. So, too, had China’s blocking of Philippine fishing and oil-exploration activities. The court ruled that Chinese vessels had unlawfully created a “serious risk of collision” with Philippine ships in the area, and that China had violated its obligations under UNCLOS to look after fragile ecosystems. Chinese fishermen, the judges said, had harvested endangered species, such as sea turtles and coral, while the authorities turned a blind eye.

China refused to take any part in the court’s proceedings and said it would not “accept, recognise or execute” the verdict. As a member of UNCLOS it is supposed to obey the court, but there is no enforcement mechanism. The condemnation of China’s actions is so thorough, however, that it risks provoking China into a response that threatens regional security as much as its recent building of what one American admiral has called a “great wall of sand”. Other countries, and America, are nervously waiting to see whether China’s furious rhetoric will be matched by threatening behaviour by its armed forces.

In 2014 the Indian government of Narendra Modi quietly accepted the court’s ruling against it in a case brought by Bangladesh over a dispute in the Bay of Bengal. But President Xi Jinping, who has supervised China’s recent efforts to reinforce its claims in the South China Sea, would find it very hard to do the same. He is preparing to carry out a sweeping reshuffle of the Communist leadership next year; foes would be quick to accuse him of selling out the country were he to appear weak.

Taiwan’s denunciation of the ruling as “completely unacceptable” will give succour to Mr Xi. The positions both of China and Taiwan are based on claims made by Chiang Kai-shek when he ruled China, before he fled to Taiwan in 1949. That Taiwan maintains the same stance under Tsai Ing-wen, who took over as the island’s president in May, is even more of a boost. Ms Tsai’s party normally abhors anything suggesting that China and Taiwan have the same territorial interests. Yet the day after the court ruling, Ms Tsai appeared on a Taiwanese frigate before it set sail to defend what she called “Taiwan’s national interests” in the South China Sea, where Taiwan controls the largest of the Spratlys.

In China, raging rhetoric quickly reached stratospheric levels. Global Times, a particularly hawkish newspaper, called the ruling “even more shameless than the worst prediction”. The government warned its neighbours that it would “take all necessary measures” to protect its interests. The social-networking accounts of Communist Party newspapers brimmed with bellicosity. “Let’s cut the crap,” said a user called Yunfu, “and show them our sovereignty rights through war.” Rumours that China was preparing for a fight ran so rife that the normally taciturn ministry of defence stepped in to deny them.

It is thought unlikely that China would quit UNCLOS: that would reinforce the impression that China is a law unto itself and do grave damage to its global image. (America has not ratified UNCLOS, but observes it in practice.) More likely is that it will set up an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea, like the one it declared over the East China Sea in 2013 after a spat with Japan over islands there. The day after the ruling, Liu Zhenmin, a deputy foreign minister, talked about China’s right to do so. Aircraft flying through China’s existing ADIZ have to report their location to the authorities or face unspecified “emergency defensive measures”. America’s military aircraft ignore this, and would do the same if a southern one were imposed. That could add to the already serious risk that the two countries’ fighter jets might end up in a confrontation.

A no-less-worrying possibility is that China might start building on Scarborough Shoal, where the court case began. Radar, aircraft and missiles based there would be a close-up threat to the Philippines and military bases that are used by American forces. In March President Barack Obama reportedly warned Mr Xi that reclamation on the shoal would threaten America’s interests and could cause military escalation.

Still, in the short term, there are reasons China might be cautious. It is hosting an annual meeting of G20 leaders in September. It is spending lavishly on preparations. The last thing it wants is for countries to boycott the event or spoil it with recriminations over its response to the verdict.

No one in the region seems to want to make life harder for China at the moment. The Philippines, for example, is going out of its way not to crow. “If it’s favourable to us,” said the new president, Rodrigo Duterte, just before the ruling, “let’s talk.”

Vietnam and Malaysia, which might conceivably launch copycat cases in the court, both put out measured statements supporting peaceful resolution of the disputes. The Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a ten-country grouping which includes four of the states in dispute with China, had little to say. Several of its members wanted ASEAN to take a firm stance against China’s claims—and an unusually strong statement released by ASEAN in June looked like the beginning of that. But it was retracted, mysteriously, within hours, making the organisation look weak and ineffective, as usual.

There may be a glimmer of hope from China itself. By one reading, it may be in the process of clarifying that the nine-dash line is less sweeping than it looks. A government statement in response to the ruling mentions both historic rights and the nine-dash line repeatedly—but always separately, without linking them. Andrew Chubb of the University of Western Australia says this might mean that China is preparing quietly to say that the line does not indicate that China has historic rights to everything inside it, but rather, that it denotes an area within which China claims sovereignty over islands.

As the verdict showed, that would still mean that many of China’s claims are inconsistent with UNCLOS. But it might result in China becoming less eager to patrol the nine-dash line right up to the edge. That may not seem much. However, in the aftermath of the ruling, the biggest question facing the countries of the South China Sea is whether Asia’s oceans will be governed by the rules of UNCLOS or whether those rules will be bent to accommodate China’s rising power. Even a small sign that the rules will not be bent as far as some hawks in China would like could be important.

选择“Disable on www.wenxuecity.com”

选择“Disable on www.wenxuecity.com”

选择“don't run on pages on this domain”

选择“don't run on pages on this domain”